Article by Diah Irawaty for SEA Junction

Source: https://padghrs.org/

In recent years in the US, the voice of post-feminism has become louder, coming mainly from middle-upper class female executives or female pop culture icons. For them, feminism is no longer relevant; women no longer face a problem of gender discrimination; they have already won the war against sexism. Post-feminism has become a real challenge for feminism, with supporters tending to forget the historical connection between the freedom they now enjoy and the long struggle of the previous generations of feminists.

Also in Indonesia, we see such post-feminist desire or, more precisely, post-New Order feminism. The new generation of gender-justice activists of the post-reformasi (Reform Era)– a transition period, which began with the toppling of then-President on 21 May 1998 and the end of his 32 years of totalitarian regime known as the New Order– rarely seem to notice and acknowledge preceding feminist movements that fought the New Order oppressive political systems. A kind of historical amnesia is exhibited by not referring to the significant contributions of the New Order generation of feminists, but rather leapfrogging to past historical figures like Kartini and her contemporaries who lived centuries before.

In fact, under the authoritarian New Order regime, our feminist movement represented a militant and critical social-political force. Stigmatized by the state as rebellious women and deemed subversive, at times accused of being associated with the banned Indonesian Women’s Movement (Gerwani), they made crucial efforts for gender equality and fought for social and political change. Within the authoritarian and superpower state, feminist movements were able to challenge the New Order’s oppressive structure. They put at risk their own safety and safeguarded the sustainability of their movement in the midst of a political environment with little if no room for freedom. They literally put their lives at risk. Julia Suryakusuma who wrote a State Ibuism criticizing the politics of gender of the New Order, for instance, was called for interrogation to the police office These pioneers with their actions and strong analytical skills aimed at destabilizing the authoritarian regime by challenging its gender politics.

Feminist movements played a pivotal role in opposing the New Order’s gender and sexual ideology of ibuism, campaigning a traditional norm of womanhood that, intersecting with bureaucratism and militarism, formed the very foundation of the regime’s hierarchical structure. They understood that the subjugation of women and the sanctioning of gender subordination was an integral part of the political consolidation of the New Orde. The State set up an ideal standard of citizenship based on gender roles and identity. Good women were mothers and wives who always obeyed their husbands and were responsible for all domestic chores. Disengaged from political and public matters and activities; they were the pillars of the nation. For men, to be included as ideal citizens with ideal masculinity, they needed to father two children, a boy and a girl, and be head of the household, as the family’s main breadwinner. If they were not in the military, they were government officers –as Suryakusuma puts it in her 1996 book.

The New Order regime controlled the narrative of the ideal gender identity and held the power to define the ideal gender roles. Among others it did so by recognizing only “traditional” women’s organizations such as Dharma Wanita and other employee wives’ organizations, while hindering feminist organizations like Kalyanamitra and Yasanti. This phenomenon confirms Ben Anderson’s thesis in his Imagined Communities (1983) that in the modern state, gender is deployed in defining and determining the category of citizenship, and to be decisive nationalism, as a source of reference to identify how someone can be included or excluded from the category of the Indonesian nation. For women, a good Indonesian citizen was a wife who was supported and backed her beloved husband by taking care of all domestic chores. Women who were involved in political movements, like those feminists, were excluded from this category of citizenship. The New Order liked to label these groups as subversive. The pivotal issue is that the state intervened to declare certain genders as norms, without acknowledging the choice of gender roles as free and identities as fluid.

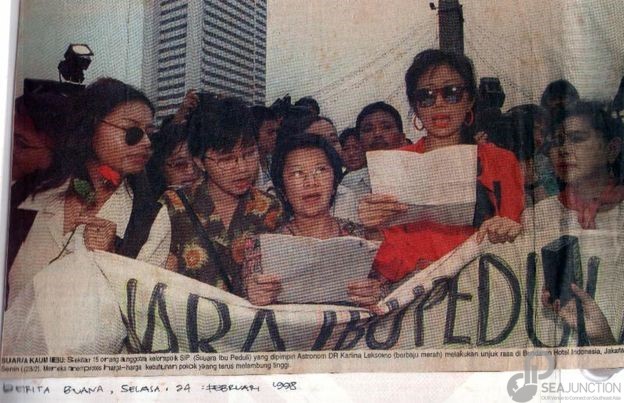

The analytical strength of the feminists in that period to understand patriarchy as integral to the New Order’s power consolidation was foundational in building and developing creative, militant, and critical civil movements. The programs and agendas they initiated were always oriented to challenging and opposing the patriarchal, authoritarian and repressive political structure of the New Order. From gender awareness training to counseling for women experiencing violence the civil movements aimed to challenge unjust social and political structure. Drawing from both native grassroots movements and international feminist theories this intellectual activism led to the development of original feminist ideas and agendas. Critique of the family planning policy coercing women to use long-lasting contraceptives reflected the activists’ ability to translate feminist knowledge into context-specific activism, and so did their opposition to the state’s developmentalism approach that led to feminization of poverty. Challenging the traditional motherhood of the New Order, Kalyanamitra organized community-based women’s groups to talk about daily life “politics.” At the edge of the New Order, Suara Ibu Peduli (The Voice of Caring Mothers) was formed and became a clear representation and articulation of the revolutionary idea of being progressive, militant, and radical mothers that was influenced by established feminist scholarship on “What is personal is political.”

The central role these feminists played in the 1998 democratic movement or reformasi is obvious proof of how strong the feminist movement was by the end of the New Order era. Their strategic participation in the reform movement resulted from their long experiences in building critical movements and their struggle against the repressive New Order regime. Those women extended their role in the political reform after the fall of Suharto by institutionalizing a number of feminist agendas, including the foundation of the National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan), the affirmative action policies in many governmental institutions and formal political processes, and the passing of an Anti-Domestic Violence Law. And to these days they strive against new totalitarian politics that hijacked reformasi as found in the campaign for anti-pornography bill, for example.

De-constructing the New Oder’s structures and its underpinning gender ideology was a vital contribution of the feminist movement whose impacts are still felt today. It is important to always keep in mind that the somewhat better status of gender justice and equality sexual freedom we enjoy today cannot be separated from the feminist contributions in the New Order. Remembering and recognizing past feminist movements is not only essential to strengthening the historical connections across generations. More importantly, it compels us to keep rebuilding solid, critical, and militant movements. We can learn from those early feminists how to sharply analyze the oppressive political structure behind gender inequality and sexual subjugation and seek a strategic way to challenge it. With all their rich experiences, feminists from the New Order era are a living book providing us with rich information and knowledge for realizing a more equitable future.

Author

Diah Irawaty is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Anthropology Department, State University of New York (SUNY) at Binghamton, New York, USA; Founder of LETSS Talk (Let’s Talk about SEX n SEXUALITIES).