Article by Ma. Diosa Labiste originally published in Women Writing Women (WWW) on 13 March, 2021

When it comes to statement masks, nothing beats the chutzpah of bilat (vagina) masks that were stitched by women inside the prisons of Iloilo City.

Hand-embroidered on cloth masks were representations of vulvas in various states and dispositions: basking in the sun, surf, and sky; in the garden with a teddy bear, rosary, and a butterfly; becoming a window to catch a glimpse of the summer sun and an ice cream cart; and regal as an odd-shaped, postmodern insect with four menacing tentacles. And many more.

The bilat masks were sewn at the height of the pandemic last year, when the country went through what was said as among the strictest lockdowns in the world, the time when cities and towns were placed on a quarantine to stem the spread of COVID-19. When masking was soon required, everyone scrambled to find precious supply of surgical masks.

This gave rise to mask-making ventures, that by using some sturdy fabrics the spread of coronavirus might just be contained. (Spoiler alert: it did not.) A “restorative social enterprise” evolved to produce bilat masks in prison during the pandemic. However, that is just one aspect of it.

The Inday Dolls Project and the vagina masks

The Inday Dolls Project and the vagina masks

The vagina masks were the offshoot of the internationally acclaimed “Inday Dolls Project,” which started in 2014 and initiated by Ma. Rosalie Zerrudo with a professorial research grant from the University of San Agustin. Zerrudo’s class project later grew with the support of local and international institutions and organizations, and with initial funds from the University of San Agustin and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts. It is both a psychosocial support and livelihood project for women detainees, specifically an art therapy that brings them income.

The healing process, according to Zerrudo, comes through telling of stories that came alive through process-centered healing workshops, poetry, prison theater performances, embroidery, and the handcrafts that they can sell – dolls, tapestries, and other needle products.

The women behind the doll project came from the cramped city jail for more than 100 women detainees living in a space intended for 30. Some 90 percent of them were facing drug charges. The youngest among them is 18, the oldest, 70. Some were mothers and breadwinners who still support their families, for example, by washing clothes inside the jail.

Zerrudo, together with Dennis Gupa, wrote about the prison project in ArtsPraxis, a journal that analyzes arts in society. Zerrudo is a cultural worker and a multimedia artist who earned her MA in educational theater from New York University while Gupa is a theater director pursuing a doctorate in applied theater in the University of Victoria.

Zerrudo, together with Dennis Gupa, wrote about the prison project in ArtsPraxis, a journal that analyzes arts in society. Zerrudo is a cultural worker and a multimedia artist who earned her MA in educational theater from New York University while Gupa is a theater director pursuing a doctorate in applied theater in the University of Victoria.

For Zerrudo and Gupa, prison arts and crafts are not only therapeutic, but they also prefigure a better world waiting for the women after their release. They argued that through the “stories of objects,” which is a creative process where the women can imagine freedom beyond prison walls through their art, they will be made whole and become productive. In other words, through the stitched dolls, the detainees undergo a self-meaning process that “gives rise to a script of possible future.” Simply put, the women became hopeful after realizing their self-worth.

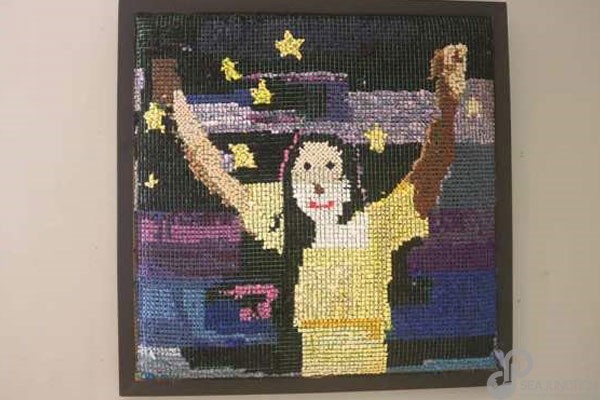

Emblematic of freedom dreamt inside the prison, the Inday dolls went on tour around the Philippines and around the world – to New York, California, Canada, Japan, and South Korea. It also earned recognition and received more funding support. Viewers of the doll exhibit were awed by the handiwork of women that demonstrates enormous potential for living productive lives, post-prison.

Emblematic of freedom dreamt inside the prison, the Inday dolls went on tour around the Philippines and around the world – to New York, California, Canada, Japan, and South Korea. It also earned recognition and received more funding support. Viewers of the doll exhibit were awed by the handiwork of women that demonstrates enormous potential for living productive lives, post-prison.

Inday dolls are so named because inday is a term of endearment and respect for a woman among Hiligaynon-speaking areas. Thus, Inday dolls embody love and geniality often associated with, and expressed through, dolls.

The bilat masks, freedom and defiance

The bilat masks take a somewhat different ground because they are out to break taboos and shatter beliefs on women’s bodies. Wearing the mask is a form of defiance of beliefs that treat women’s bodies as commodities and their private parts, a booty. Wasn’t it that Duterte himself urged soldiers to shoot women communist rebels in the vagina and also said that he, then a mayor, should have been the first to rape an Australian missionary. Women’s reproductive organs are also subjected to pernicious controls and appropriations by religion, the state, and media in ways that are too many to be included here.

Like the dolls, the vagina masks are remarkable portraits of a safe and healthy world. The colors, the vignettes, and the scale of some pudenda altogether convey that even in the lingering pandemic, the world would be a lot better, happier, and generous any time soon. For example, one of the masks feature a vagina of radiating colors with half of the sun on one side and the gloomy prison bars with coronavirus in the opposite side. Surrounding it are ocean waves, a flock of blue birds near the sun, and a blue and red hearts near the prison bars. What could have the woman been thinking when representing freedom on the cloth mask? Another interesting piece is a winking vagina with bemused expression that is both funny and self-deprecating.

Like the dolls, the vagina masks are remarkable portraits of a safe and healthy world. The colors, the vignettes, and the scale of some pudenda altogether convey that even in the lingering pandemic, the world would be a lot better, happier, and generous any time soon. For example, one of the masks feature a vagina of radiating colors with half of the sun on one side and the gloomy prison bars with coronavirus in the opposite side. Surrounding it are ocean waves, a flock of blue birds near the sun, and a blue and red hearts near the prison bars. What could have the woman been thinking when representing freedom on the cloth mask? Another interesting piece is a winking vagina with bemused expression that is both funny and self-deprecating.

Double lockdowns

Since March 2020, the women prisoners experienced a lockdown within a lockdown. The double lockdown is lethal in an event of a coronavirus outbreak in overcrowded prisons. Philippines jails are currently 500 percent beyond their capacity with some 134,000 detainees.

Overcrowding worsened since 2016 when the Duterte administration embarked on the so-called war on drugs with mass arrests in hundreds or in thousands. The courts have not kept up hearing the drug cases. On April 2020, barely a month into the nationwide quarantine, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism noted that the country’s jails are a COVID-19 timebomb, leading some humanitarian groups to call for the release of elderly, sickly and reformed prisoners, including sickly political prisoners. But the call was unheeded by the government. In fact, during the first few weeks of the nationwide lockdown, some 20,000 were arrested for quarantine violations. While many were briefly held, the risks of infection remained because the comings and goings in the jails could easily lead to coronavirus outbreaks.

Bodies in prisons are packed to transform them into what French social theorist Michel Foucault termed as docile bodies. These bodies are molded by disciplinary regime of prisons, programming prisoners to become obedient individuals. In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault said the scale of control is down to the level of movements, gestures, and attitudes, where overcrowding assures the control’s success.

Bodies in prisons are packed to transform them into what French social theorist Michel Foucault termed as docile bodies. These bodies are molded by disciplinary regime of prisons, programming prisoners to become obedient individuals. In Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault said the scale of control is down to the level of movements, gestures, and attitudes, where overcrowding assures the control’s success.

Bodies in confinement learned to adjust to the physical constraints but slowly, this blueprint of domination takes hold and individuals submit to strict subjection. The interventions of Zerrudo and other volunteer artists through theater workshop seek to restore the agency of women’s bodies, and reverse a condition where “the body is walled, and the morality of women prisoners are subjected into confined rehabilitation and management.”

The question that guided Zerrudo and Gupa’s research is how might the women in prison exercise their sense of freedom? The answer is through stories that they represent via objects like dolls, tapestries, and other sewing crafts, aside from the theater performances and poetry that they staged. The bilat masks are among the objects that contain stories or “object-stories” that project images of freedom through meditative needle art. Thus, even through double lockdowns and fears of COVID-19, the masks double as a searchlight that beams hope.

The images of freedom offered by the statement masks are what the women prisoners desire. Buying and wearing the bilat masks means supporting their wishes, among them their early release from jail.

Photos are from the Facebook page, Inday Doll: Hilway Art Project. More information can also be found in Instagram: Indaydolls #indaydolls #bilatseries #bayaninginday

Source:

Source: