Articles by Tom Vator originally published in Nikkei Asia on October 20, 2022

Children are seen at the Mae La refugee camp in April 2022. Three generations of Burmese children, may of whom do not speak Burmese, have grown up in the camp, the largest of nine refugee camps established in the 1980s along the Thai-Myanmar border inside Thailand. ( Courtesy of Visual Rebellion Myanmar)

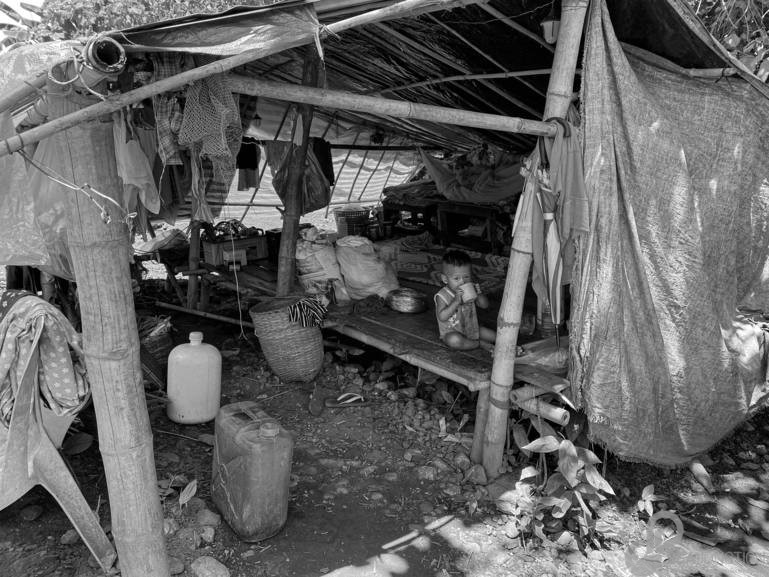

“If you exhibit a photo like this (of a child in a makeshift hut) or if you criticize the military while you are in Myanmar, that might be the last day of your life,” said Burmese photographer Aung Naing Soe. His work is featured in “Endless Escape: Fleeing Myanmar to Thailand,” a photo exhibition documenting refugees trapped in the borderlands between Thailand and Myanmar. The exhibit runs until November 6 at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center.

Organized by SEA Junction, a Bangkok-based foundation that promotes cultural interactions in Southeast Asia, the work by photographers Yan Naing Aung, Zin Koko, media collective Visual Rebellion Myanmar, and Aung Naing Soe documents the plight of villagers displaced by the conflict between December 2021 and March 2022.

After Gen. Min Aung Hlaing instigated a military takeover on Feb. 1, 2021, and overthrew the government of Aung San Suu Kyi, the military sought to put down a popular uprising. While the world has since turned its attention to other crises, Myanmar’s population continues to fight one of the world’s cruelest regimes. Thousands of protesters and ordinary citizens have been tortured and killed. High-profile activists and parliamentarians have been executed. Nearly 13,000 people have been incarcerated.

The United Nations estimates that nearly 1 million people have been internally displaced since the takeover and tens of thousands of people have either left the country or are camping along the 1,500-kilometer-long border with Thailand.

There have been refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar border since the mid-1980s. Over the decades, tens of thousands of people crossed in and out of Thailand to escape fighting in the long-running conflict between Myanmar government troops and ethnic minority armies in the eastern parts of Myanmar, particularly Kayin (formerly known as Karen) state. The nine camps inside Thailand currently hold 91,000 people according to the U.N., with a further 5,000 refugees outside the camps who are classified as urban refugees.

Inside the “Endless Escape” exhibition, now being held at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center, in October. (Photo by Tom Vater)

A child sits in a makeshift shelter at an informal settlement along the Thai-Myanmar border in December 2021-January 2022. (Photo by Yan Naing Aung)

Visual Rebellion contributed images from Mae La, the biggest camp, established in 1984, which houses 40,000 people, highlighting the sad reality of the “Endless Escape.”

“The children we talked to in this camp speak Karen, a bit of Thai and a bit of English, but they don’t speak Burmese. When asked where they come from, they point at the camp behind them and say, ‘Mae La, Mae La.’ That’s all three generations of people have known,” said a Visual Rebellion co-founder.

Since the takeover, more refugees have arrived in the border camps. The Thai government estimates that around 17,000 people crossed into Thailand between February 2021 and February 2022. Most of them are villagers from the Karen, Karenni and Shan states as well as anti-government protesters and journalists.

Children play at an informal settlement along the Thai-Myanmar border in December 2021-January 2022. (Photos by Yan Naing Aung)

Children play at an informal settlement along the Thai-Myanmar border in December 2021-January 2022. (Photos by Yan Naing Aung)

“That figure is likely to be a vast underestimate. It’s politically dangerous for the Thai government to quantify the amount of people who come over,” said Patrick Phongsathorn, with Fortify Rights, a Thai-based human rights organization.

“Thai authorities have housed these refugees in what they call ‘temporary safety areas,’ but they have not allowed the [U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees] or other aid agencies access. It’s questionable how these areas have been run, what aid has been given, what kind of protection screening mechanisms, if any, have been put in place.”

Thailand has not ratified the 1951 U.N. convention on refugees. “Thai authorities regularly breach the international legal principle of non-refoulement, a key principle when handling people who fear for their safety,” explained Phongsathorn, “In April 2021, we documented at least 2,000 people being forced across the river into Karen state. In late September this year, a group of Karen students was filmed being forced back.”

A woman and her grandchild in a makeshift temporary camp on the Thai-Myanmar border in December 2021-January 2022. (Photo by Aung Naing Soe)

According to the Karen Human Rights Group, Thai authorities sent back 300 Karen students fleeing fighting in Karen state. When they were sent back across the river, two of the boats collided and one sank, although no one died.

“The people caught up in this conflict did not want to leave their homes. They have no choice. If they stay, they might die at any time. So when they cross the river, if they don’t have any support, how are they going to survive?” said Yan Naing Aung, one of the photographers.

In early October, Ma Theingi, a 25-year-old Karen nurse affiliated with Myanmar’s civil disobedience movement, was shopping for groceries in a border market. She saw a Thai police raid looking to arrest illegal immigrants. In a fit of panic, she jumped into the Moei River and drowned, leaving a 4-year-old child in Karen state.

Political considerations dictate what happens along the border, according to Phongsathorn.

“Thailand has hosted pretty sizable refugee populations for 40 years and they really want to avoid having that situation again with the recent refugees. Thailand’s laws and policies criminalize seeking refugee status. That pushes people to lead a life in the shadows, under constant fear of extortion, arbitrary arrest and detention and forced return. That in turn drives people into modern slavery. The Thai government’s relations with the Burmese junta also play a part in how refugees are treated.”

Yet Thailand remains the easiest escape from the conflict. Thai civil society, along with members of the Burmese diaspora, have long provided new arrivals with food and other necessities.

Soe described shooting images of thousands of villagers fleeing airstrikes in Karen state in December 2021 and arriving in Mae Sot.

Volunteers from Thailand and Myanmar cross the Moei River to deliver supplies to refugees trapped inside Myanmar in December 2021-January 2022. (Photo by Zin Koko)

People prepare and pack food on the outskirts of Mae Sot to be delivered to informal settlements along the river in December 2021. (Courtesy of Visual Rebellion Myanmar)

“Many local Thai families along the border were cooking for refugees and delivered aid supplies. We embedded with them and crossed back into Myanmar to bring supplies from monasteries and families. Even Thai factory owners let their laborers help Myanmar refugees. We are much safer here than people inside Myanmar or along the border. We’re so grateful to the Thais,” said Soe.

Phongsathorn suggests changes in the law may have an effect on the ground, “Thailand recently passed anti-torture legislation. Article 13 of that legislation puts the international legal principle of non-refoulement into Thai law. Hopefully cases will now be put forward, so we don’t see the kind of incidences of forced return we saw in late September.”

Soe worried that “Myanmar is forgotten. There are many international organizations and experts working along the border, but there’s no action. There’s no international support. There are no campaigns and there’s no recognition. Every single person in Myanmar is heartbroken.”

“Endless Escape: Fleeing Myanmar to Thailand” was open daily, except Mondays, at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. through November 6, 2022.

Source: Bangkok photo exhibit portrays plight of Myanmar refugees – Nikkei Asia