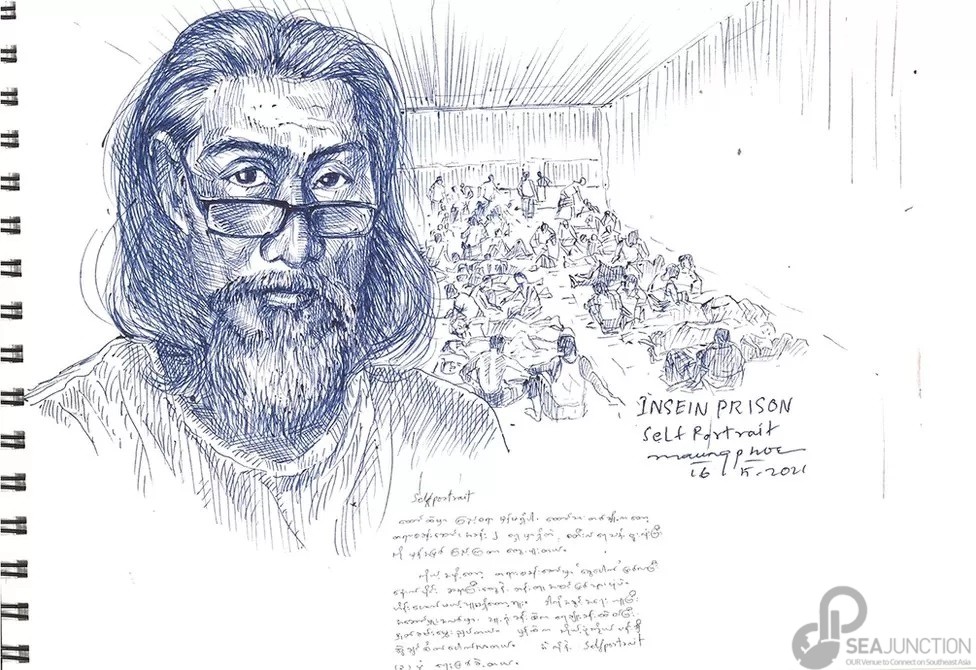

Maung Pho, who was jailed at Insein, recorded life inside with his pen

Phyo Wai Hlaing, a 21-year-old wi-fi technician, had been missing for a week in July 2021 when his father received an anonymous phone call telling him to go to a bridge far from his neighbourhood in Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon.

There the street food vendor was told that his son had been arrested. A few days later he read about it in the state-run newspaper.

Phyo Wai Hlaing was among a group of 29 who were arrested and accused of storing explosives for use in terrorist attacks and for supporting People’s Defence Force insurgents who are fighting Myanmar’s military government.

Also in that group was Si Thu Aung, a 19-year-old, first-year engineering student. Witnesses told his mother they saw him being taken away by police the day after Phyo Wai Hlaing went missing.

Both young men had disappeared into Myanmar’s gulag, a network of prisons and interrogation centres used for decades to detain and torture dissidents.

At its heart is Insein prison, a name that has come to symbolise the repression imposed by successive military regimes. That is where Phyo Wai Hlaing and Si Thu Aung first went after being sentenced to seven years in prison.

The BBC has been speaking to some of the detainees’ families, and to Maung Pho, an artist, who used his six-month incarceration to make detailed drawings of life inside Insein, which he has now been showing at exhibitions in Thailand.

Maung Pho had some special privileges. He was allowed to use the warden’s bathroom, which had a mirror, to trim his beard. On one of those occasions, he drew this self-portrait

Stamped into the map of northern Yangon like a giant wheel, Insein prison is one of the more sinister legacies of British colonial rule in Myanmar. It was built in 1877 in the form of a panopticon, giving a central guardhouse a clear view to all corners of the “wheel”. It is Myanmar’s largest prison. Most political prisoners serve at least part of their sentences there, usually the many months in detention before their trials. Some do not survive the experience.

“I was hoping to rely on him when he graduated from university,” says Si Thu Aung’s mother. “My neighbour tried to comfort me, and I realised that there was now no-one else to help my family, since my husband is ill and bed-ridden. So, I told myself I still have to look after my younger son and husband, and support my son in prison.”

From that point both families’ lives would be consumed by the challenge of supporting their sons inside one of the world’s most barbaric prison systems.

Three weeks after his arrest, Si Thu Aung’s mother got a phone call from Insein telling her to send food and money for him. Without such support the conditions and food inside are so poor the health of prisoners can deteriorate badly. She says she has been spending 140,000 kyats ($67) a month to send him food parcels, which is about two-thirds of what she earns from selling steamed soya beans on the street.

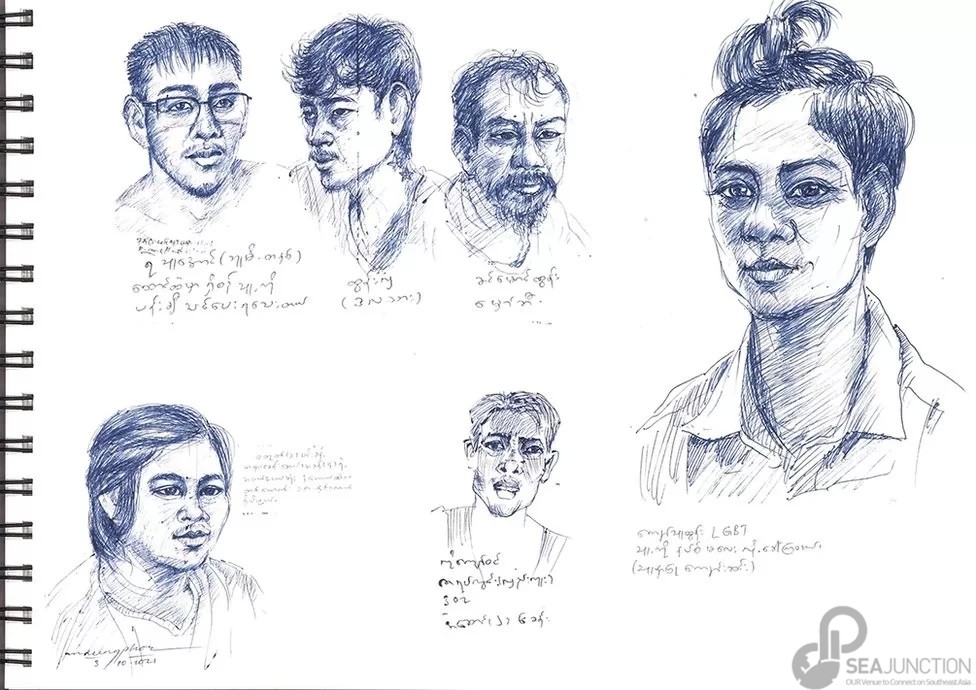

Maung Pho also sketched other inmates. He taught Ye Thu Aung (top left) how to draw. At 18, Wa Toe (bottom left) was one of the youngest prisoners. Kyaw Thu Htun (bottom right), who identified as queer, was known as ‘nurse’

Phyo Wai Hlaing’s two trials lasted three months. His father only got to see him twice, about a month before the verdict, and hear for the first time what his son had been through. He had been extensively tortured in five different interrogation centres, including Ye Kyi Ai, a notoriously brutal one near Yangon international airport.

“They took him to a morgue and showed him all the decomposing bodies there, telling him ‘your life is now worthless. We can kill you for less than the cost of a bag of charcoal’. He had a gunshot wound in his leg because he had been shot when he was arrested. They had rolled iron rods on his shins, he had a large swelling on the back of his head, a dislocated arm and a dislodged disc in his spine. His memory was no longer good – even now he still cannot remember people’s names.”

His father has already sold all the family’s jewellery to support his son in prison. They have one piece of land, in his mother’s village, which they will also have to sell. After that they will have to manage on what he earns selling mohinga, the fish soup typically eaten for breakfast in Myanmar.

Lawyers for the two young men say they charge as little as possible, usually just the cost of their transport to court, to help the families. But guilty verdicts are inevitable; they say they have no chance of getting their clients acquitted. We are more like social workers or counsellors, one lawyer said – “all we can do is provide some comfort to our clients, who are rarely allowed to see their families”.

(L) Thant Zin Toe, a bureaucrat, 18 or 19, who had joined the anti-coup protests in 2021; and Kyan Min Htun – bookworm, aerospace engineering student and protest leader

Myo Myint, another street vendor, was able to see for himself the conditions his son Lin Lin Htet experienced in Insein; he was arrested with him, in October 2021, and released 10 months later.

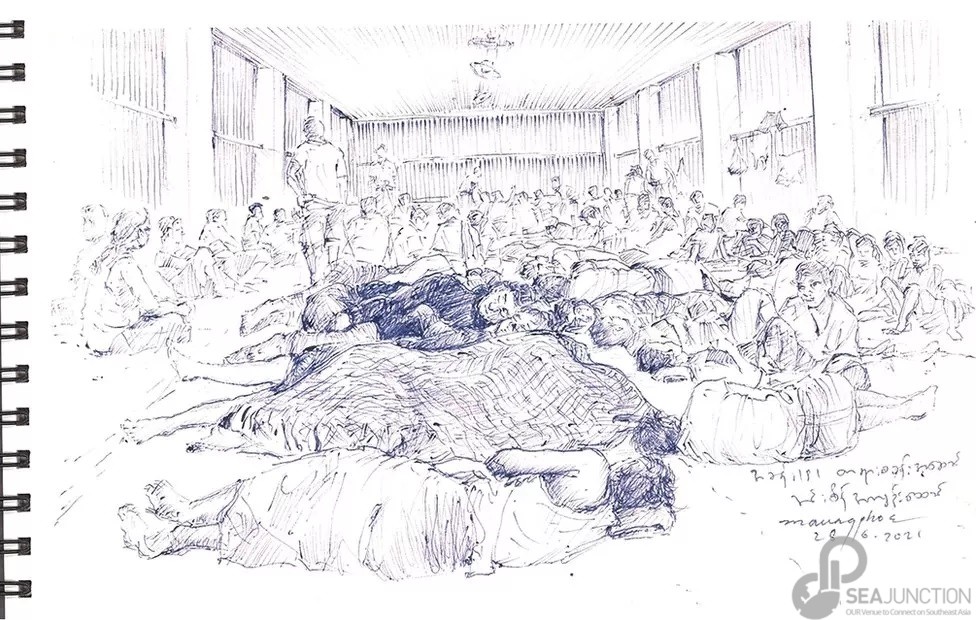

“Our cell had 100 people in it, in a space only 5x6m (16×19 feet). We all have to sleep on our sides and face the same way. Those who can afford to pay 100,000 to 150,000 kyats a month can get a better spot to sleep.” He says he saved his money to pay the guards for better treatment for his son.

Lin Lin Htet was interrogated for five to six days. “He was beaten pretty badly,” says Myo Myint, who shared his cell for their first weeks in prison.

“When he came out of the interrogation centre he could not walk or stand, two people had to drag him to the cell. I saw many wounds on his body. Burns on his chin and legs. Two toenails had been pulled out. His whole body was in pain. All I could do was apply some pain-killer cream I had. My son said they grabbed his hair and smashed his head against the wall or table. He can’t hear properly any more.”

Maung Pho drew Kyi Pauk who would often lie down or lean on a wall because of injuries from lead pellets

Artist Maung Pho was more fortunate. When he was dragged from his home in Yangon by soldiers on the night of 7 April 2021 he assumed it was because of a graffiti illustration he had made showing the coup leader Min Aung Hlaing committing suicide while standing next to Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

“They kicked my head and told me to try running, so they could shoot me,” he said. “‘We are no longer under the rule of high-heels’ [ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi], they shouted, ‘this is now the rule of military boots’. I thought it would be my last moment.”

But at the police station he realised it was less serious. He had been detained after a complaint by his local neighbourhood administrator over something he had said.

The cramped conditions he witnessed in Insein made Maung Pho want to record them with his pen: “The room we slept in could fit, at most, 150 people, but there were 474 sleeping there. Can you imagine it? People had to lie down like tinned fish.”

His skill as a draughtsman won him a few privileges, like being given fresh fruit juice by one of the guards whose portrait he drew. But most of the time he had to hide his pens and illustrations, which he drew on scraps of paper that came in the food parcels families sent to the inmates. These he cut up and smuggled out by concealing them within the walls of the cardboard boxes in which inmates leaving the prison carried their possessions.

Maung Pho was released after six months, and made his way, like so many other Burmese dissidents, to safety in Thailand.

Maung Pho said more than 400 prisoners slept in a room meant for 150 people

The families of Lin Lin Htet, Phyo Wai Hlaing and Si Thu Aung now live in the hope of an amnesty for their sons, or for their sentences to be reduced. Lin Lin Htet has already had his seven-year sentence cut by six months.

“My life has really suffered since he was arrested,” says Si Thu Aung’s mother. “He used to help me out a lot. He likes reading, and got top grades in his university entrance exam. I want him to be well-educated. I don’t want him to end up like me, with a life that is tough and poor.”

Phyo Wai Hlaing’s younger brother, who is eight years old, goes to prison as often as he can to see him.

The two brothers share the same birthday, and are close, says their father. They also send him two food parcels a month, which he usually shares with his cellmates.

Phyo Wai Hlaing has asked them to save their money and just send him one parcel. He has told them he is committed to continuing with his political work, opposing the military government. But he has advised his younger brother to stay away from politics, telling him “Once you start, it is not easy to get out.”

Additional research and reporting by Lulu Luo in Bangkok

Source : https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-65959508