Public Lecture Report by Catharina Maria[1] and Rosalia Sciortino[2]

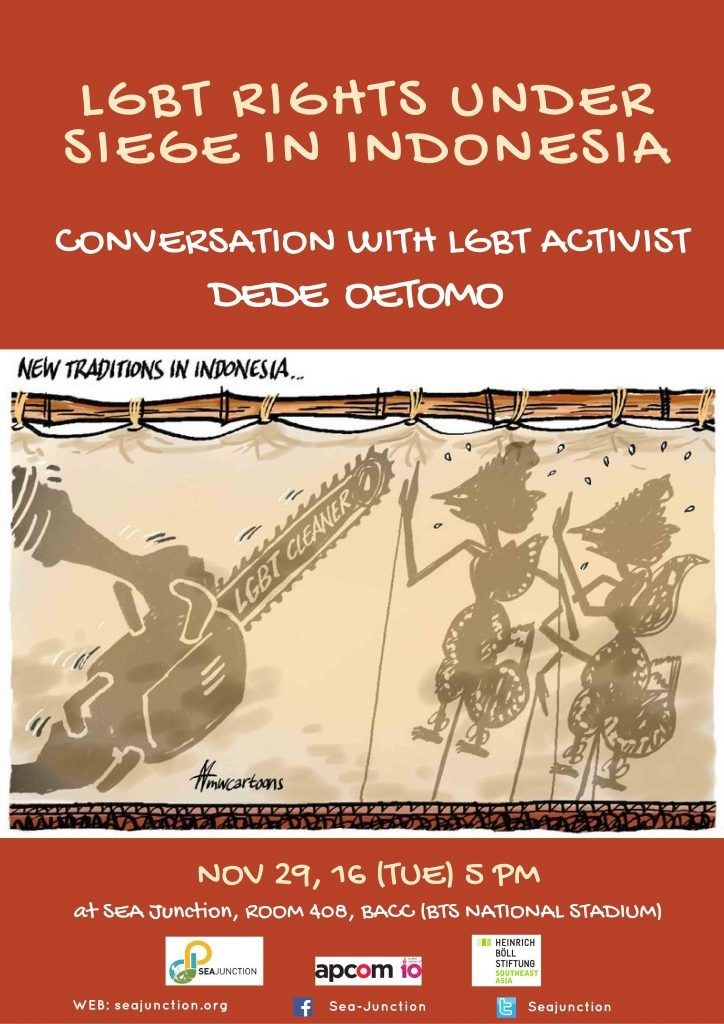

The last week of November 2016, Bangkok witnessed the sprouting of rainbow colored flags as participants gathered from all over the world to attend the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans* and Intersex Association (ILGA) World Conference. A satellite event that attracted much attention was a public lecture on “LBGT Rights Under Siege in Indonesia” organized on the afternoon of 29 November 2017 by SEA Junction in collaboration with APCOM[3] and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southeast Asia and open also to non-ILGA participants. The speaker was renowned Indonesian activist Dédé Oetomo, founder of GAYa NUSANTARA, one of the first LGBT organizations in Indonesia, Chair of APCOM Regional Advisory Group and a member of the Advisory Council of the Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies.

Rosalia (Lia) Sciortino Sumaryono, the Founder and Executive Director of SEA Junction and Associate Professor, Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University opened this public lecture by welcoming the more than 70 participants who crowded SEA Junction’s premises at the Bangkok Arts and Culture Center (BACC). She then briefly introduced the organization and its partners, the purpose and modalities of the event and the speaker.

Two Waves of Attack

Dede Oetomo at the center surrounded by representatives of SEA Junction, APCOM and Heinrich Böll Stiftung

When given the word, Dédé Oetomo stressed that the focus on the LGBT situation in Indonesia is because of the increased level of intolerance and homo- and transphobia in recent months and the need to raise awareness about it regionally and globally. As a case in point, he mentioned the arrest a few days before of 13 gay men who were meeting up in a middle-class condo following a raid by the Islamic Defender Front (FPI), a hardline Islamic group, and the accusation of their conducting an orgy. Although they were released the next day, as there was no proof of sexual misconduct, the expanding vigilantism of FPI is worrisome. In the past, FPI and similar groups have targeted public LGBT events forcing their cancellation, including the 2010 ILGA Asia Conference in Surabaya, but as they are allowed a greater role in the current political climate in Indonesia, they may be testing the ground in private settings too, further limiting the space for LGBT people.

After this premise, Dédé Oetomo began with his PowerPoint presentation and identified two waves of attacks to LGBT people that encroached on their security and rights. The first wave that created “Indonesia LGBT crisis” started in the first quarter of 2016 when ministers, government officials, influential Islamic leaders and experts made strong statements against LGBT in the media. The initial assertion was by Research, Technology and Higher Education Minister, Muhammad Nasir, who declared in January that universities had to uphold standards of ‘values and morals’ and accused a small informal student group named the Support Group and Resource Center on Sexuality Studies (SGRC) of the University of Indonesia to promote LGBT activities just by studying sexuality. Mahfudz Siddiq, the chair of Commission I in charge of defense and foreign affairs at the House of Representatives, followed suit by stating that LGBT issues can damage national security, identity, culture and faith of Indonesians. While the Defense Minister, Ryamizard Ryacudu, described efforts to recognize LGBT rights as an attempt by Western nations to undermine Indonesia’s sovereignty, a proxy war to brainwash Indonesians, and LGBT organizing as “worse than a nuclear warfare”. Not to talk about the Mayor of Tangerang, Arief R Wismansyah, who said that “feeding your baby with formula and instant noodles will turn them gay”! More generally there were calls for criminalization of LGBT behaviors and activism and forced “rehabilitation” for LGBT people, including by the Indonesian Psychiatric Association as it proclaimed homosexuality a “mental illness”.

These unfounded and prejudiced statements and the homophobic climate they created have had far reaching consequences, fostering an environment where LGBT can be easily exposed to abuses and curtailment of their basic freedom. For example, Indonesia’s only Islamic boarding school or pesantren for transgender women (called “waria” in Indonesian), which had managed to operate for many years in Yogyakarta, was forced to close because of protests by radical groups supported by the same neighbors who in the past had co-existed in harmony with the pesantren and its activities.

After a few months of relative quiet, in June 2016 a second wave of attacks to restrict sexual behavior (and not only for LGBT) was launched at the Constitutional Court. Two conservative organizations, the Aliansi Cinta Keluarga (Love Family Alliance, AILA) and Gerakan Indonesia Beradab (Civilized Indonesia Movement) asked for a judicial review to broaden the definitions of adultery (article 284), rape (article 285) and same-sex intercourse with minors (article 292) in the Criminal Code. The proposed changes are strongly opposed by human rights organizations, the National Commission on Violence Against Women and the Human Rights Commission, and youth sexual and reproductive health and rights groups, since, if passed, all sexual intercourse outside marriage, consensual or not, would be outlawed and prosecuted. In particular, it would criminalize consensual adult same-sex sexual behavior, with penalties of up to five years in prison.

By September, after an uproar about underage prostitution in Bandung, there was a request by police to the Ministry of Communication and Information that 16 dating apps and websites be banned, although most seem to still be active. International donors have also been prevented from funding LGBT organizations and some of their staff have had problems renewing their visa.

Dédé Oetomo talking to the audience

Looking Back

In analyzing these two waves, Dédé Oetomo, a linguist by training, started from the terminology used. He found it interesting that the previously poorly known term of “LGBT” has been used rather than the many local idioms as if to deny homegrown (indigenous?) sexual practices and identities. Literature and historical sources show however that in the past there was more openness about gender identity and sexuality. Bugis culture in South Sulawesi, for example, recognized five genders, men, women, transman, transwoman and bissu (a spirit medium metagender). Serat Centhini, a 19th century Javanese text tells the story of two wonderers and their various adventures including their sexual encounters and experimentations.

Later times saw puritanism spread through colonial Victorian norms and Christian values adopted by local elites as well as due to the spreading of purist Islam. Modernism, either secular or religious in nature, brought a redefinition of morality according to the so-called “adat ketimuran” (Eastern customs) which uprooted more liberal local sexual mores.

During the more than 30 years of President Suharto’s New Order[1] (1965-1998), “State Ibuism”[2] –the dominant gender ideology defining women as wives and mothers– prescribed patriarchal and hetero-normative behavior standards that were used as a form of social control, and which left homosexual Indonesians outside national belonging. Nonetheless, as long as they were in the shadow, they could live according to their preferences. For instance, trans women in full drags have for decades worked in beauty salons and been considered part of the community.

The fall of President Soeharto in 1998 and the new democracy brought a liberalization of Indonesian society. Democratic, human rights-based culture, including feminism, sexual reproductive rights and health and sexual orientation and gender identity activisms thrived. Emboldened by the introduced reforms and an unprecedented media freedom, LGBT people felt they could be more open about their identity and let their voices be heard. The number of LGBT organizations increased rapidly and today there are two national networks and over 200 organizations with 120 verified and registered (although the actual purpose is not explicitly stated), not counting the myriads of groups in social media.

Conservatizing Indonesia

More recently, it has become clear that old systems are very entrenched in society and conservative values are far from disappeared. The augmented level of LGBT organizing eventually encountered opposition in a context wherein religion and religious groups increasingly play a political role, and politicians make use of religion to mobilize society to support their causes. LGBT’s demand for legitimacy came to be perceived and be presented by conservative parties as a threat to the existing social order and its hetero-normative template. The US Supreme Court decision on marriage equality boosted the anxiety about a more visible LGBT population and the accusation of their wanting to follow suit even if Indonesian LGBT organizations actually do not prioritize marriage in their advocacy.

Upcoming fundamentalism is contributing to a renewed emphasis on the view that “Islam does not allow LGBT lifestyle” and the dismissal of the contrary view by progressive religious scholars, like Siti Musdah Mulia that bravely explained “how Islam is not against homosexuality”. In a very Javanese way, President Joko Widodo recently stated to the BBC that minorities should be protected and he expressly mentioned LGBT people –the first time an Indonesian President did so — only to add that “Islam does not allow it (LGBT lifestyle).” Rejection is not exclusive to Muslims. Christian churches in Indonesia have started to organize revival retreats against LGBT people who have been branded ‘the work of the devil’ In Hinduist Bali, while same-sex marriage ceremonies for tourists and mixed couple may still be conducted, they have to be done in secrecy as religious leaders and authorities have pledged not to tolerate them.

Analysts have also pointed out that LGBT people have become an easy scapegoat in the creation of a public enemy to be used to provide distraction from more serious economic and political matters and/or for politicians and aspirant ones to gain support from more conservative groups. Few months before the first wave of attacks against LGBT people there had been efforts of reviving the fears of “communists” –in a country where communism is illegal and more than a million suspected communists and their sympathizers were killed in 1965 — as a security threat to national unity and thus halt the growing demand for accountability of the 1965 killings and other past abuses. However, as such charges seem somewhat outdated to the general public, LGBT people were made into the new bogeyman. Recently, the new target are ethnic and religious minorities as the Chinese, non-Muslim frontrunner in the Governor race and current Governor of Jakarta, Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama has been named suspect in an ill-founded blasphemy allegation so as to end its candidacy before the elections in February, which he is expected to otherwise win. No wonder then that media surveys speculate that the three most despised groups in Indonesia are Chinese, LGBT and communists.

In spite of these worrisome trends, Dédé Oetomo see it as an opportunity that, because of the current crisis, the LGBT issue is now “on the table” and can be openly discussed in the public and policy spheres. He remains optimistic as he believes that Indonesian society is not per se homophobic and LGBT people have come a long way in terms of organizing. In his view, there are many layers of discourses on LGBT in the country and what needs to be done now is navigating and positively influencing them.

What now?

During the discussion between the participants and the speaker, the LGBT crisis in Indonesia was further discussed and there were reflections on what could be done to cope with it.

Reacting to expressions of dismay at the seriousness of the crises mixed with admiration for the speaker’s constructive attitude, Dédé Oetomo stressed that from the outside Thailand is seen as a paradise for LGBT communities, and Indonesia is accused of having become like North Korea. Yet many LGBT people in Indonesia feel they are freer in Indonesia than in neighboring Malaysia, and even Singapore. This is not to dismiss the risks and it needs to be recognized that some places are not safe for LGBT people in Indonesia. Rather, it is meant to recognize that intolerance at the political level is not the only reality for LGBT people in Indonesia and that local communities are generally inclusive, if not politicized.

Regarding what could be done to address the situation, there was agreement that not much can be expected from the country leadership, as even those who are not against the LGBT community are pragmatic in what political battle to choose and LGBT are not high on their list. Similarly, there is not much hope in the intervention of ASEAN as a supranational regional body, since it is bound by non-interference and not too sensitive to LGBT rights. A regional approach could still be useful, however, to compare to neighboring countries. Experiences of other Southeast Asian countries that are more open including Vietnam and Thailand, can be used in advocacy efforts to dismiss the rhetoric of LGBT people and behavior as alien to Asian values. Regional alliances can also be very useful as a source of solidarity, support and funding.

Coalitions are also important at the country level. Although LGBT organizations have made major headways in number and quality, alone and not united they would not be able to realize the positive changes needed. Institutionally, they need to strengthen their management, increase the reach of their membership and enhance the level of organizing of the overall LGBT community. There is now an opportunity to involve high-ranked corporate LGBT people who have become more willing to participate since they no longer feel immune from the general hysteria. It will also be important to work closely between gay, transgender and lesbian organizations, and to ensure that the most vulnerable are protected. During the first wave, many lesbians got ugly comments on their social media accounts, but not the gay men.

Externally, LGBT organizations need to work cross-sectorally with other groups to advance a pluralism agenda. At times that may not be easy as not all ethnic and/or religious minorities are necessarily open to LGBT, but with the radicalization of the country it will be key to join forces. Collaborations with disadvantaged groups may be strategic too to broaden acceptance, such as the work initiated in the 1990s to reach out to the labor and peasant movements. Lesbian groups have been working closely with women workers in the factories, and Indonesian domestic workers overseas. Also, it is crucial for LGBT organizations to continue building on current collaborations with sympathetic journalists, women, human rights and sexual and reproductive health organizations and movements, and institutions that have been providing information and services for LGBT communities.

In view of the nature of the attacks, LGBT organizations will have to enhance their communication skills and use of social media both to control rumors and to spread their message across. They also needs to become more knowledgeable of Indonesian Law and study the Indonesian civil and criminal codes, and become empowered to go to court whenever their rights are entrenched. They also will need to monitor the Constitutional Court judicial review closely not to allow repressive control of sexuality. If not, the rainbow’s colors may wane in Indonesia.

About SEA Junction

SEA Junction aims to foster understanding and appreciation of Southeast Asia in all its socio-cultural dimensions –from arts and lifestyles to economy and development. Conveniently located at Room 408 of the Bangkok Arts and Culture Centre or BACC (across MBK, BTS National Stadium) SEA junction facilitates public access to knowledge resources and exchanges among students, practitioners and Southeast Asia lovers. For more information see www.seajunction.org and join the Facebook group https://www.facebook.com/groups/1693055870976440/.

[1] Catharina Maria, independent consultant with expertise in peace building, gender, and capacity building

[2] Rosalia Sciortino is the Founder and Executive Director of SEA Junction (seajunction.org) and Associate Professor, Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University (www.ipsr.mahidol.ac.th/).

[3] Asia-Pacific Coalition on Male Sexual Health Foundation (www.apcom.org).

Further reading:

Emont, Jon, A Happy Warrior in a Faltering Battle for Indonesian Gay Rights, New York Times, The Saturday Profile, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/20/world/asia/indonesia-gay-rights-dede-oetomo.html?_r=1

Human Rights Watch, “These Political Games Ruin Our Lives”: Indonesia’s LGBT Community Under Threat, 10 August 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/08/10/these-political-games-ruin-our-lives/indonesias-lgbt-community-under-threat

Mann, Tim, Q&A: Dede Oetomo on the LGBT panic, March 17, 2016,

http://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/interview-dede-oetomo-on-the-lgbt-panic/

Oetomo, Dede, The Power of Knowledge: Towards the Transformative Use of Science in Empowering Marginalised Groups in Society, 19 September 2016, https://www.facebook.com/notes/dede-oetomo/the-power-of-knowledge-towards-the-transformative-use-of-science-in-empowering-m/1087627224606521/

Oetomo, Dede and Hendri Yulius, What’s behind Indonesian authorities’ desire to control LGBT sexuality? The Conversation 23 September 2016, http://theconversation.com/whats-behind-indonesian-authorities-desire-to-control-lgbt-sexuality-65543

Sutthida Malikaew, Will the First Ever Transgender MP Be the One and Only in ASEAN? http://seajunction.org/will-first-ever-transgender-mp-one-asean/, 4 August 2016, SEA Junction Opinion http://seajunction.org/will-first-ever-transgender-mp-one-asean/