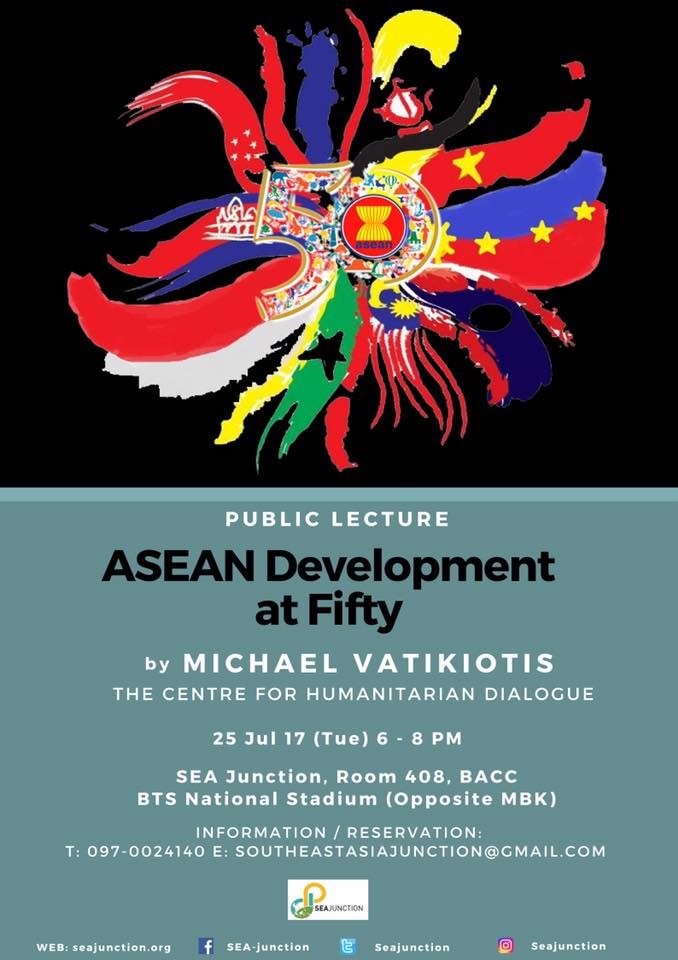

Public Lecture by Michael Vatikiotis on July 25, 6:00PM-7:30PM at SEA Junction

Good afternoon.

Good afternoon.

Thank you, Lia for the brief introduction. I want first to expand a bit on my background. My sojourn in Southeast Asia spans altogether four decades. I arrived first as a student here in Thailand in 1979. That was four years after the end of the Vietnam War, the tail end of the Cold war era in the region.

I spent two years in Chiang Mai researching my PhD on the history of the city, then returned to London where I became a journalist at the BBC. A couple of years later I was fortunate to be appointed Jakarta correspondent, which allowed me to return to SE Asia. I never left.

In 1987, I joined the Far Eastern Economic Review as Jakarta bureau chief. I subsequently moved to the Kuala Lumpur and then Bangkok bureaus for the magazine, before being appointed Managing Editor in 1999 and moving to Hong Kong. From there I was privileged to edit the magazine and continue reporting until the American owners, Dow Jones, closed the publication in its weekly form in 2004.

I then entered the strange and interesting world of mediation in armed conflict.

I have spent the past dozen years or more inhabiting the world of armed conflict and political violence. I have worked on resolving conflict in Indonesia, in the Philippines, in Myanmar and here in Thailand. Unlike my stint as a journalist, I cannot claim much success. Success in journalism is measured in stories and news coverage; conflict is perpetual and rarely gets resolved. That’s why, writer that I am at heart, I wrote a book about my experiences.

“Blood and Silk” is a journey through Southeast Asia, not in the conventional sense as a casual traveller might see the region. Instead it is a journey through a long experience of observation: my own experience over four decades as student, journalist, writer, and then as a mediator striving to end armed conflict. It takes the reader through the historical origins of state and society, the formative influences on modern nationhood and in turn how I believe this historical legacy has affected contemporary political trends and generated chronically high levels of popular struggle and violent conflict.

Based on this experience, I would like to give you a snapshot of where I think ASEAN is at 50.

Look around and it is hard to deny that Southeast Asia is a region of great opportunity. A region of 605 million people, growing overall at an average of a little below 5%. 120 billion dollars in foreign direct investment in 2015. The ten countries of ASEAN have not only enjoyed economic growth for much of the past three decades, but none of them have gone to war with each other. It’s easy to forget that ASEAN was forged in 1967 here in Bangkok in the burning embers of the Cold War; Indochina was a cauldron of conflict. Just two years earlier, Indonesia had invaded Malaysia. For all the subsequent rhetoric of economic cooperation, ASEAN was above all a mechanism for ensuring regional security – and it still is.

By the far the greatest of ASEAN’s achievements, therefore, has been to prevent war between its component member states. Yet the paradox is that there are many wars waged within.

For Southeast Asia is home to the longest running civil wars in the world. In Myanmar to the West, more than twenty ethnic armed groups battle the central government and have done for the most part since independence in 1948; In the Southern Philippines, the Muslim Moros have been fighting for autonomy since the mid 1960s in a conflict that has cost more than 150,000 lives. Indonesia and Thailand are also home to violent insurgencies seeking to address grievances built around notions of self-determination that hark back centuries before the modern period.

This landscape of insecurity is sometimes hard to grasp when you consider how well Southeast Asia has fared in social demographic terms. Adult literacy averages more than 90%, unemployment is comparatively low, and life expectancy plumbs above 65 years.

But peer a little closer and after 50 years it is fair to ask why a quarter of the population of the Philippines and Myanmar are still living below the poverty line; in more developed Indonesia and Thailand, this figure is above 10%. Only Malaysia and Vietnam maintain poverty rates below 10%.

But the really significant indicator is that of economic inequality. In Indonesia, for example, real poverty rates have fallen over the past decade, yet 1 percent of the richest people still control about 50% of the wealth. In the Philippines, it 25 families own as much wealth as 70 million Filipinos. Here in Thailand, income per capita in Greater Bangkok is more than double what it is elsewhere in the country, indicating a high level of inequality.

Now consider that more than any other part of the world today that claims to adhere for the most part to democratic principles of government and has the GDP to do so, Southeast Asia fails chronically to deliver on the promise of popular sovereignty.

The latest map of freedom generated by the US-based Freedom House shows that, apart from Japan and India, the whole of Asia is considered either ‘not free’ or ‘only partly free’. That includes the Philippines and Indonesia – both semi-democracies, only partly free.

Remarkably, this democracy deficit cannot be explained away by the kinds of chronic war and related social dislocation afflicting troubled parts of Africa and the Middle East. Quite the reverse, for the past four decades Southeast Asia has been at peace and growing a solid 6 to 8 per cent per year.

The challenges to better government and long-term peace stems from three sources, in my view.

The first is the friction impeding transition to democracy. In Southeast Asia, the prolonged monopoly of power and resources in the hands of traditional mostly urban elites has sustained strong, authoritarian government. Peaceful, often reasonably fair elections may be regularly held, but political change is often elusive – as in Myanmar where the military retains a quarter of seats in parliament, or in Thailand where conservative jurists strive for a version of democracy that suits the Thai way of life, history and culture. Or in Cambodia, where the opposition is threatened with violence if it wins elections.

And because popular demands cannot be accommodated in a broadly inclusive way, people are forced into protest and militancy. That is why we see the emergence of pernicious destabilising conflict and corrosive divisions in society fuelling extremist views. In the Philippines, a communist insurgency has fought for comprehensive social and economic reform for more than half a century; here in Thailand repeated efforts to enfranchise upcountry voters using meaningful policies of re-distribution have generated a violent backlash and a prolonged period of military rule.

The second challenge is to maintaining the stability of ASEAN’s social fabric. One of my biggest worries is the threat to ethnic and religious pluralism in the region. For there has been a loosening of the bonds of tolerance and inclusion underpinning social stability in Southeast Asia. Identity politics is on the rise. Following a global trend, growth in religious orthodoxy has hardened the boundaries between different religious communities and generated high degrees of intolerance and exclusivity that increasingly fuels violent conflict. In Rakhine State, a million stateless Muslim Rohingya are in a volatile state of neglect living amid a jingoistic Buddhist Rakhine population that wants them all to leave and is willing to fan the flames of religious tension, if necessary across the country, the prevent Rohingya being granted citizenship.

The sense of separate instead of shared identity has taken root in more integrated societies such as Indonesia, where all of a sudden Muslim Indonesians want to be governed by fellow Muslims and were prepared to oust a popular city governor simply because he was a Chinese and Christian. Often alarming levels of economic inequality have fuelled these tensions. Evictions, poor healthcare and access to services, even in central urban areas of Jakarta are alarmingly high. But politics has played a role: the selfish motivations of elite political actors who mobilised hardline Islamic forces to weaken a popular President and make space for themselves. In the process, they have fuelled a trend in Indonesian society that increasingly divides religious communities.

In neighbouring Malaysia, the trend towards ethnic and religious integration has similarly been reversed by powerful state and political forces that seek to preserve power by reinforcing boundaries between different elements in society, not dissolving them. When I lived in Malaysia in the mid-1990s there was talk of a truly Malaysian society; today many ethnic Chinese want to leave and more liberal Malay Muslims worry about the increasing Arabisation of Muslim society.

Degraded pluralism creates a permissive environment for violent extremism to take root. Looking around the region there has been a serious uptick in ethnic and religious intolerance leading to tension and violence that has opened the space for extremist activity. In part, this has come about because of the failure to address long-running historic grievances on the margins of the region. The ongoing siege in Marawi City in the Philippines is a direct outcome of the failure to implement a peace agreement between he GRP and the MILF. The lack of a tangible peace dividend after two decades of negotiations for peace have opened a portal that IS and a host of homegrown jihadist elements are using to try and establish a caliphate in SE Asia.

The large numbers of people crossing borders in search of refuge and economic opportunity make Southeast Asia one of the hardest to protect from violent extremism. Meanwhile, deteriorating social conditions driven by alarming income inequalities ensures there are cohorts of young people susceptible to violent ideology.

Rather than address this challenge with policies aimed at shoring up traditions of tolerance, Southeast Asian governments have become prone to conservative impulses serving the ends of power. Malaysia has allowed Muslim clerics to declare liberal Muslims deviants and non-Muslim Chinese who question Islamic law worthy of being slain; a senior Indonesian security official quite recently said that lesbians and gays constitute a threat to national security. Really?

Together with the alienation and fragility generated by protracted sub-national conflicts and the chronic impunity with regard to abuses of power and human rights, little wonder that Southeast Asia is susceptible to becoming a haven for violent extremists feeding off social division and disaffection.

The third challenge to peace in ASEAN after half a century in my view is external. The spread of conservative Islamic dogma and extremist ideology fuelled by the contest between Saudi Arabia and Iran and the rise of China as an economic and military power are two of the most significant developments Southeast Asia has experienced since the Pacific War and the end of the colonial era in the mid-twentieth century.

Saudi Arabia and Iran seem determined to escalate their struggle for domination of the Muslim world, which can only mean continued funding for religious schools that spread conservative preaching, which in turn creates a petri dish environment for the incubation of hard-line extremist thinking. It is simply a waste of time for governments to make efforts to prevent violent extremism through programmes of de-radicalisation if at the same time a blind eye is turned to the steady erosion of the legal and institutional moorings of tolerance that Saudi Arabia in its existential struggle with Shiite Iran is underwriting.

Muslim nations in Asia have little or no influence over either country – though they should since the majority of Muslims in the world now reside in Asia. But if there is no political will to defend constitutional rights and freedoms and instead manipulate race and religion for political ends, there will always be a steady stream of people attracted to violent extremist ideology.

Meanwhile, efforts by Western powers, principally the US, to balance and moderate China’s burgeoning influence in Asia are generating geopolitical friction and turning Southeast Asia into a cauldron of superpower rivalry. Over the past five years we have seen China and the United States increasingly spar over geo-politics in Southeast Asia. China’s importance to ASEAN is evident as there is almost USD 500 billion in bilateral trade compared with USD 8 billion in 1991. The US has encouraged regional states to challenge claims of sovereignty to small islands in the South China Sea, which in turn has provoked China into a vigorous defence of these claims and an aggressive escalation of tension.

And even if China’s growth grinds to a halt, or if the country suffers a catastrophic internal collapse – not unprecedented over the long arc of Chinese history – Southeast Asia will be affected due to the probable migration of Chinese to the region, much as they did at the end of the Ming dynasty in the seventeenth century and then more spectacularly after the collapse of the Qing dynasty at the end of the nineteenth century.

To sum up, then: The immediate future of Southeast Asia looks certain to be characterised by enduring struggles for equality and freedom. The experience of the past four decades indicates that even with improved access to the power of modern communications technology and media, the success of these struggles is doubtful, mainly because the power holders have all the guns and control access to justice. I ultimately think that the slow response of government to grievances and use of divide-and-rule tactics to undermine opposition will force communities and groups to look after themselves and defy the powerful centre.

I’ll end with a passage from the end of the book:

Towards the end of 2016, as I was putting the finishing touches to this book, I took a stroll along the magnificent waterfront in the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, which sits at the junction of the Bassac, Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers. It was the start of the rainy season and the waters of the Tonle Sap, which lap the city’s shore, were a muddy red. For centuries Cambodians have relied on the swollen waters of the Tonle Sap to do a unique reverse flow at the end of the rains, flooding sizable areas of land to provide sustenance in the form of fish and plentiful water for irrigation. For this reason, the Tonle Sap is literally a river of life. It was a Sunday afternoon, a cooling breeze blew off the water, and Cambodians of all ages thronged the newly renovated corniche. Some huddled over decks of cards with fortunetellers, others brought flower offerings to the highly revered Preah Ang Donker shrine that sits in front of the royal palace facing the waterfront. Young boys dangled fishing rods in the river and surfed their smartphones; nearby their would-be girlfriends preened and snapped selfies. Young mothers propped their babies up on the iron railing facing the river and older men puffed along in bulging t-shirts and trainers.

This colourful tableau of civic contentment left me feeling momentarily upbeat. For how improbable was it that a country reduced to a ruined mass graveyard in 1979, the year I first arrived in Southeast Asia, could within a generation, seem so prosperous and peaceful. The country was literally rescued by a huge international effort and for all the factional rivalries that accompanied the aftermath, seeds of democracy were sown and appeared to bloom, allowing the economy to boom – at least that was the outside perception. But Cambodia in the democratic era, as Sebastian Strangio, the author of an authoritative biography on Prime Minister Hun Sen, aptly put it is ‘a graveyard of outside perceptions.’ For despite the calm and serenity of that Sunday afternoon stroll, sentiment below the surface seethed with anger and people spoke fearfully of the future in hushed tones. There was also a subdued anger, evident when hundreds of thousands of people followed the funeral cortege of a popular political commentator, Kem Lay, who was gunned down on 10 July 2016 – the funeral procession stretched for more than 40km. ‘I know they are angry,’ said one senior government official, ‘because in this country those in power believe it is their right to have the lion’s share of resources – it has always been this way’. So it is with Cambodia’s tenacious Prime Minister Hun Sen, so it was with Suharto of Indonesia, with Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia, and with Thaksin Shinawatra of Thailand; all these leaders promised their people happiness and prosperity but in the end left them divided and deprived. They brandished the symbols of wise, munificent leadership, but enriched their families and brooked no dissent. They left anger and conflict in their wake.

No longer the most war-ravaged countries in Southeast Asia, Cambodia now holds the title of the most corrupt. Is this the fate of Southeast Asia: locked in a cycle of relentless tragedy, partial recovery, then relapse? ‘We have a saying in Cambodia,’ the senior government official told me over a long breakfast the morning after my stroll; ‘when the water is high the fish eat the ants; when the water is low, the ants eat the fish.’

Thank you for listening.