Panel discussion report by Farid Khan[1] and Rosalia Sciortino Sumaryono[2]

Panel discussion report by Farid Khan[1] and Rosalia Sciortino Sumaryono[2]

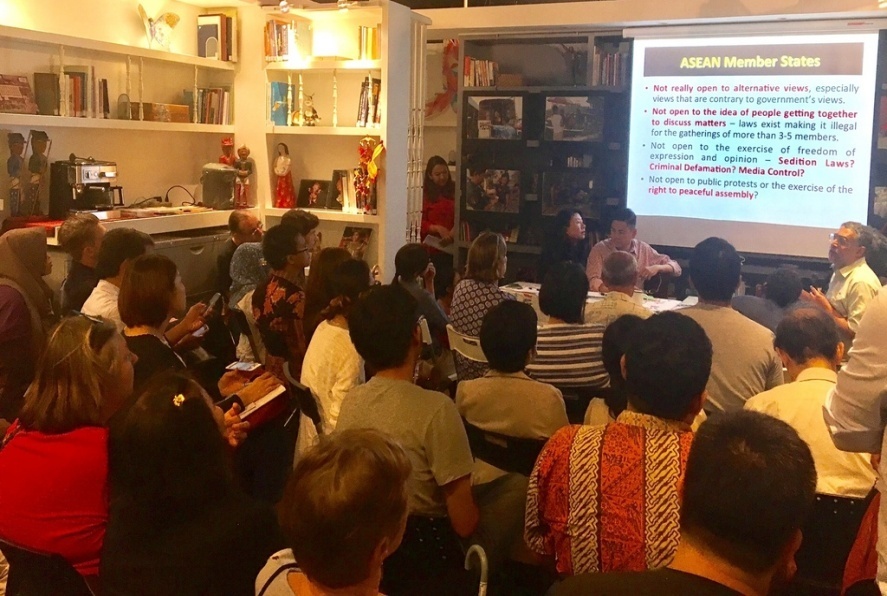

On 12 October 2016, SEA Junction organized a panel discussion titled “ASEAN Governance: Is There a Role for Civil Society?” in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southeast Asia. More than 70 participants, many of them from Southeast Asia, filled SEA Junction premises at the Bangkok Art and Cultural Centre (BACC) in Bangkok, Thailand to eagerly listen to the speakers and exchange views on the challenge of establishing a more representative governance system for ASEAN as a “people-centered” inter-governmental institution.

The panel was chaired by Rosalia Sciortino Sumaryono, Founder and Executive Director of SEA Junction and Associate Professor, Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University and consisted of speakers from academia and civil society and a representative of the ASEAN Secretariat, whose unit oversees relations with civil society organizations (CSOs). Respectively, they were Moe Thuzar Fellow, Lead Researcher (Socio-Cultural Affairs), ASEAN Studies Centre and Coordinator, Myanmar Studies Programme; Charles Hector, Human Rights Defender and Member of the Malaysian Bar and Romeo Arca Jr., Assistant Director/Head of the ASEAN Secretariat’s Community Relations Division.

After welcoming all those in attendance, the Chair framed the discussion topic by stating that although progress has been made towards more close-tied regionalism and more sophisticated mechanisms for joint governance, ASEAN relationship with civil society remains fraught with tensions. While ASEAN is keen to collaborate with the business sector and closely engage with it at all levels, civil society groups have little space to formally interact with ASEAN with the possible exception of the ASEAN Civil Society Conference/ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (ACSC/APF) and a number of commissions with limited authority devoted to specific topics and groups namely the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) Meetings, the ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children (ACWC) Meetings and the ASEAN Forum on Migrant Labour. At the same time, civil society groups are struggling to find an effective strategy on how to engage with ASEAN processes and how to advance their demand for representation in overall ASEAN governance structures, beyond the formality of the annual ASEAN leaders-CSO interface of less than one hour. As an illustration of worsening relation, the last ACSC/APF took place in Dili, Timor Leste instead of in Laos as it would have been customary and the usual ASEAN leaders-CSO interface was dropped at the Vientiane Summit.

Taking it from these introductory comments, the first panelist Moe Thuzar provided the broader picture of ASEAN-civil society interaction. She noted that since civil society started to be reckoned as a significant force in the region about 30 years ago, ASEAN’s relationship with NGOs, think thanks, academic institutions and other similar entities has been uneasy notwithstanding that in ASEAN documents the vision is to engage them at various levels. She stressed that the expectations on the two sides diverge on how civil society should be engaged in inter-governmental processes, with ASEAN expecting civil society to support ASEAN decisions and civil society wanting to have a larger role in consultation and decision-making processes. When ASEAN interacts with civil society groups it is mostly in a functional and pragmatic way making use of their technical expertise and/or their presence on the ground, such as in the control of infectious diseases or during post-disaster rehabilitation efforts.

A greater role for civil society and more attention to human rights is limited by the diversity of national positions, since ASEAN governs by consensus and ‘non-interference in the internal affairs of one another’. It is important to realize in this context that the way ASEAN relates to civil society reflects the relationship of individual Member States with their citizens. Also ASEAN bureaucratic processes are lengthy and it takes time to shift positions and move a specific agenda forward in view of the many push and pull factors in reaching consensus. For progress to happen it will have to be at multiple levels and entail strengthening of quality relationship between governments and between governments and their citizens as well as of the process mechanisms themselves.

In spite of the overwhelming challenges, NGOs, academic institutions and think tanks should not dismiss the importance of a more proactive participation and continue to work at the national as well as at the regional level to ensure civil society becomes an integral part of the future of ASEAN. In doing so, they need to take a long-term approach. To show that change is possible, albeit it takes time, Moe Thuzar concluded citing Myanmar as example: from 2007 to 2014 Myanmar has made exponential progress in expanding accountability and civil society voice as evidenced in the World Bank Governance Index for ASEAN countries.

|

|

|

| Three panelists in the discussion (left to right) Moe Thuzar, Romeo Arca Jr. and Charles Hector with panel chair | ||

In his follow-up presentation of ASEAN position, Romeo Arca Jr agreed with Moe Thuzar that ASEAN formally recognizes the value of civil society engagement as vital to the political, economic and socio-cultural communities that constitute the three pillars of ASEAN. The main institutional reference is Article 16 of the ASEAN Charter stating that “ASEAN may engage with entities which support the ASEAN Charter in particular its purposes and principles” wherein the term “entities” implies all organizations that are not government bodies including parliamentarians, think tanks, academic organizations, business organizations and CSOs. This translates into commitment to engagement with civil society in higher levels and, in Arca’s view, the cancellation of the ASEAN Leaders-CSO interface in Laos will likely not be repeated next year when the Philippines holds the chairmanship of ASEAN.

That said, Romeo Arca Jr also shared the view of the previous speaker that more needs to be done to establish an enabling environment for meaningful and constructive interaction. Two key issues require attention to this end: firstly, for civil society to engage with ASEAN they need to adhere to the “Rules of Procedure and Criteria for Engagement for Entities Associated with ASEAN” set out in 2014 by the Committee of Permanent Representatives to ASEAN (CPR) in accordance with the ASEAN Charter. CSOs and other entities that want to be associated and engage with ASEAN have to apply for accreditation and this requires an endorsement from the relevant ASEAN Organ and/or Sectoral Body besides meeting a number of criteria proving their accountability and strategic expertise. Agreed modalities include dialogue, consultation, interface, seminar, workshop and forum and, once accepted, it is up to ASEAN to decide upon review whether the association may continue or be ended.

Second, engagement of civil society happens more deeply at the sectoral level such as in agriculture, health or tourism. It is at that level that there is more space for entities to become involved and where gradually more space is being shaped. It remains challenging to engage civil society in the overall governance of ASEAN since Member States seems to take the fact that ASEAN is an inter-governmental body to exclude representation of non-government entities. He concluded that for more space to open up it will require a change of position and the setting up of mechanisms that engage civil society in governance in a win-win situation.

The last panel speaker, Charles Hector questioned some of the assumptions and statements of previous presentations starting from an analysis of the different interpretations of the term“civil society” used to group together very diverse organizations including NGOs, community groups, trade unions, foundations. professional organizations, religious associations, and justice and human rights organizations (more recently renamed human rights defenders). ASEAN leaves the definition quite open focusing on “non-profit organisation of ASEAN entities, natural or juridical, that promote, strengthen and help realise the aims and objectives of the ASEAN Community and its three Pillars”. Yet, a look at the organizations recognized so far will show that advocacy and human rights groups are lacking.

Interestingly, by embracing also natural CSOs, ASEAN takes a more progressive stand than their Member States in recognizing that most CSOs in Southeast Asia, and especially those concerned with justice and human rights, are not registered being often of a temporary nature to act speedily for a cause; because of complex and controlling registration processes; and also due to weariness of State intervention. ASEAN’s seemingly inclusive approach, however, does not translate into practice. For accreditation, the minimum requirement consists of a copy of registration papers and financial statements, and since “natural” CSOs lack such papers, their proclaimed recognition by ASEAN does not actually happen. As Hector emphatically stated in Malaysian “Cakap tak serupa bikin” (Action is not same as talk).

Government practices in the region also reveal that ASEAN Member States are not ready to engage with CSOs and uphold human rights. Individually they are not really open to alternative views and have restrictions to the exercise of freedom of expression and opinion and of the right to gathering and peaceful assembly. Regionally, ASEAN’s tenets of consensus and of non-interference preclude individual members as well as ASEAN as a whole from expressing disapproval of human rights violations in the region. It is therefore a question whether there is any value for CSOs to try to engage ASEAN to end injustice and human rights abuses that are happening in ASEAN Member States.

On the side of the CSOs, the transformation and professionalization of CSOs from volunteer and often self-funded groups to sophisticated organizations increasingly specialized and dependent on donor funding is leading to the marginalization of more grass-roots and advocacy-oriented entities. Few well-funded organizations monopolize the debate and engagement with ASEAN , claiming to ‘represent’ civil society at the exclusion of smaller, and often more vocal, groups. Barriers to participation are also the high costs of ASEAN venues and of travel and lodging and the use of English full with acronyms and references not understandable to more local institutions and most ordinary persons. Collective action is also challenged by CSOs’ increasing specialization and their sectoral focus limited to advancing a particular cause (say indigenous rights, LBGT rights, women’s rights or freedom of expression) rather than broader rights and governance issues.

A worrysome change is that the nature of ACSC/APF has been transformed. Initially the forum served to bring as many CSOs together to discuss, debate and formulate a common stand and demands to be handed over to ASEAN and its Member States and, more recently, also to be expressed orally in the added interface of CSO representatives and ASEAN. However, in the last two fora in 2015 in Kuala Lumpur and 2016 in Timor Leste the statement was sent to ASEAN even before the participants arrived. The latest two CSO Statements have become “very ASEAN friendly” no more daring to highlighting wrongs and making specific demands, and the forum itself has become more a place for governments and ASEAN to speak to CSOs rather than the other way around.

Engagement with ASEAN to remain real and meaningful may have to occur outside of ACSC/APF and other formal processes. The focus of CSOs may need to change, not just focusing on “ASEAN” per se, but rather to build solidarity among CSOs of ASEAN Member States (and beyond) to challenge injustices happening in one country or even in one factory or community. The role of CSOs is in this context is not to compromise their principles and causes to please ASEAN or governments, but to empower and develop greater support in the struggle for human rights and justice, not just amongst CSOs but among the peoples of ASEAN. Governments cannot ignore the will of their people, likewise ASEAN. The methodology of engagement needs to change towards engaging ASEAN people instead of only engaging ASEAN, ASEAN Committees and Working Groups and ASEAN governments if we want to realize an ASEAN Community led by its people.

The follow-up discussion among the participants and with the panelists continued the debate on what can be realistically expected by ASEAN in view of its modalities of consensus and non-interference as well as the shrinking space for civil society in the region. In conclusion, the Chair summarized the various positions and reflected that the engagement of civil society is not for the sake of engagement itself but finalized to the greater goal of changing society for the benefits of disadvantaged and excluded groups.

In this context, civil society groups will need to diversify their strategies wedging whether for the particular issue they wish to promote it is strategic to engage with ASEAN within its limited parameters or it makes more sense to work outside of ASEAN scope concentrating at the national level in devising collaborations with the media and other potential advocates to advance their causes with the public and with their governments. In the realization that the socio-economic and political environment in each country shape Member States’ positions in ASEAN, work needs to be directed at national change. Whether the optimistic view of better times for ASEAN- civil society interaction with the Philippines taking up the ASEAN Chair –as traditionally could be expected– is justified is still to be seen in view of the current rights averse climate in the Philippines.

For now, the more central issue of ensuring democratic governance at ASEAN on terms that allow for a diversity of position will require a longer term commitment and a multitude of approaches and innovations. There will need to be self-reflection of all parties involved on what can be done to carve more space for a genuine dialogue that do not necessarily require civil society to conform. At the end of the day, if ASEAN is to achieve inclusive and more equitable growth new governance and decision-mechanisms, developed by all relevant parties, will need to be put in place to guarantee representation of and accountability to the most disadvantaged. Moreover, ASEAN’s vision of a people-oriented regional community can only be realized with the acknowledgement of different views and positions and the representation of the diverse constituencies that compose this complex region.

[1] Farid Khan, Independent Researcher, SEA Junction Volunteer

[1] Farid Khan, Independent Researcher, SEA Junction Volunteer

[2] Rosalia Sciortino Sumaryono, Founder and Executive Director SEA Junction (www.seajunction.org) and Associate Professor Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University