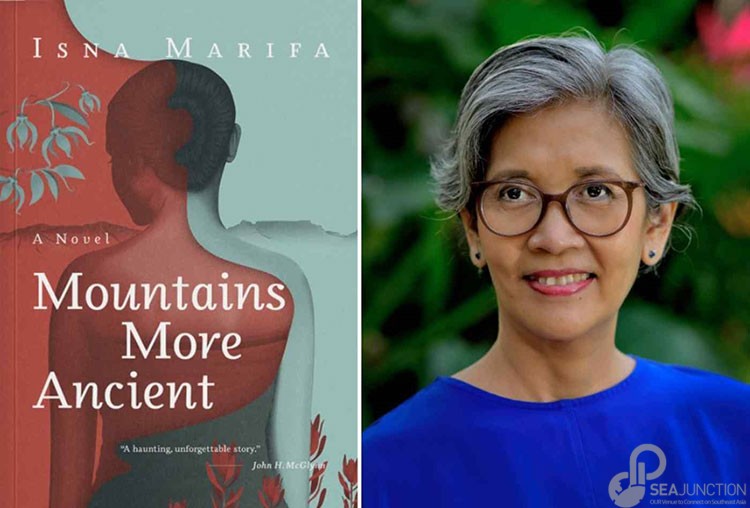

Isna Marifa’s novel “Mountains More Ancient” relates the history of Southeast Asians enslaved in Africa, treading a path of graceful reconciliation with history’s complexities. (Nikkei montage/Courtesy of Isna Marifa)

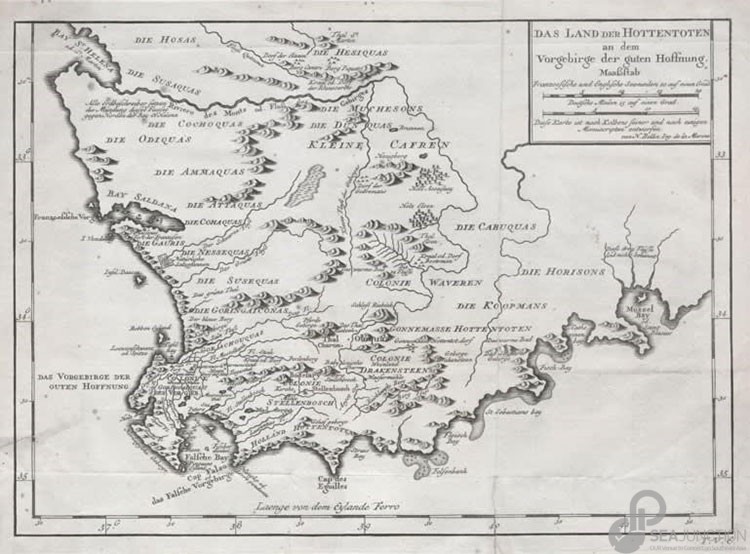

In the 17th and 18th centuries, thousands of people from what is now Indonesia and Malaysia were taken as slaves to the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. Descendants of this population, who mixed with Europeans and other Asians, came to be known as Cape Malays.

Founded in 1652 by the Dutch East India Company in what is now Cape Town, South Africa, Cape Colony was a way station between the Netherlands and the largely Dutch-controlled East Indies, now known as Indonesia. It provided a break in the long and perilous sea voyage from Asia to Europe, and beyond the haven there was good farmland for former employees and settlers. The Cape’s indigenous population, the San and Khoe speakers, were decimated by war and disease brought by the Europeans, making imported labor logical and necessary for the colonists.

Cape Colony was set up to exploit Asia, and was served by Asians who through debt and misfortune had become chattel without rights or recourse to justice. Over time Javanese carvers, Turkish horse grooms, and Gujarati sailors were thrown together with the exiled followers of rebellious princes and religious leaders, from places like Maluku and Sulawesi, who had been shipped off to the Cape as political prisoners. Many were incarcerated, like Nelson Mandela, the first president of post-apartheid South Africa, on Robben Island.

“Mountains More Ancient,” a recently published novel by Indonesian author Isna Marifa, explores this fascinating story. The novel begins in the mid-1700s and charts the life and times of a Javanese man, Parto, who falls into debt and is sold by a loan shark to the Dutch. Believing that he might end up on a plantation in Sumatra, Parto brings along his young daughter, Wulan, but they end up in Africa, with no chance of returning home.

The gradual colonization of Java by the Dutch and the formation of the Cape Malay community weave through Parto and Wulan’s tale. But “Mountains More Ancient” is about everyday events and people, its author more interested in relatable instances than the grand march of history. It is an effective and appropriate way to tell a painful story, which allows for dignity and compassion — a gracefulness that extends even to the declining fortunes of a Dutch settler family.

This 17th-century painting depicts a senior merchant of the Dutch East India Company and his wife, attended by a slave, in what is now Jakarta. At that time, the city was known as Batavia and was the capital of the Dutch East Indies. (Getty Images)

These means of storytelling emerge within a lineage. Marifa’s father, Soedjatmoko, was a prominent Indonesian diplomat. One imagines that her upbringing, which included time in Japan and the U.S., afforded many insights into the impact of large political events on private lives.

At the end of World War II, with armed conflict escalating in Indonesia, Soedjatmoko espoused dialogue with the colonial Dutch. He was charged with taking Indonesia’s case to the United Nations, becoming a delegate to the U.N. Security Council, where he remained throughout the Indonesian independence struggle. Soedjatmoko’s career was dedicated to public service and open discourse, as diplomat, journalist and academic.

The first time Marifa visited South Africa she explored Bo-Kaap, a historic Cape Malay district of Cape Town, and was haunted by words, flavors and faces — traces of her native Java. A chance sighting of a slave register at a museum inspired her to write the novel; here were lists of individuals, with their names, ages, origins and prices, a people taken from across Indonesia. Their fates were unknowable; all that could be said with certainty was that they had helped to form a community that embodied hope and resilience, and the coming to terms with a difficult past.

“Mountains More Ancient” was written with the intention of reconnecting two communities through a shared culture and history. It is an inception story for a people whose delicate relationship to the Cape is evident in the name of their historic cemetery, Tana Baru — Malay for New Land — which can be read as both statement and wish.

Brightly colored houses in Bo-Kaap, a historic Cape Malay district of Cape Town. (Getty Images)

“Mountains More Ancient” is syncretic throughout: down to small details like the pairing of Javanese flowers, soka and kantil, with those of the Cape, luise and hangertjie. The titular mountains of the novel link the fertile volcanic slopes of Java with the impervious stone of the Cape’s Table Mountain; the effect is not so much binary as metamorphic.

Marifa’s insights and evocations of nature befit her expertise in helping institutions and individuals to understand environmental issues. It is apt that within the narrative we hear of the arrival of coffee in Java, heralding political upheaval, and of the fear of extractive agriculture leading to loss of biodiversity and disease. The environment is a story and symbol of transmutation. “After all,” Marifa said at a launch event for the book, “mountains are sacred the whole world over.”

The history of the Cape Malays is not well known in Indonesia; it has, in Marifa’s words, “fallen through the cracks.” It is salient that, although occurring in Africa, the situation described in “Mountains More Ancient” transplants features of Southeast Asian slavery, a multifaceted subject that has been generally overlooked. Until the 19th century slavery was rife across Southeast Asia, where it was an integral part of the economy and warfare, owing in part to the low population density of the region in premodern times, which led to a chronic shortage of labor.

Slavery came in many different forms, ranging from enforced labor and conscription that was tantamount to slavery, to the enslavement of war captives. There was wholesale transplanting of communities, and slavery was often linked to debt. Until the mid-19th century individuals could be owned, gifted, and bought and sold at market.

A 1757 map showing the Cape of Good Hope. (Getty Images)

Slavery in Southeast Asia was not exclusively race-based, which might be why the legacy of slavery in the region is less pernicious than elsewhere. However, ancient practices may explain nightmarish throwbacks found in today’s fisheries industry, in human trafficking and in the sex industry. While popular Southeast Asian memory is hazy on the existence of slavery, it lingers beneath the surface in place names and linguistic traces, and less perceptibly in social dysfunction and disparities.

“Mountains More Ancient” could easily have accentuated the horrors and dehumanizing aspects of slavery, but instead it leads to freedom — from servitude, hatred and the weight of history. The manner in which this is achieved is recognizably Southeast Asian, in its most positive form: It involves a celebration of diversity and compassion. For instance, Marifa invests her characters with qualities such as nrimo and pasrah — quintessentially Javanese concepts meaning acceptance and surrender to what the universe has to offer.

Parto’s resignation to hardship looks like docility but it is strength; he transcends hopelessness by assimilating the unfamiliar land, and through creative acts, like the carving of southern African timber into a delicate Javanese box — a labor of love that speaks of wealth and continuity, a set of values to pass on and keep alive.

Although this book does not wear political colors, it can be regarded as part of the discourse surrounding colonialism and slavery. It might be suggested that storytelling itself can help renounce victimhood and confer power. With this simple idea in mind, Marifa’s Javanese represent focal points rather than faceless entities at the mercy of rapacious colonizers and slavers.

They are afforded agency and empathy for their political errors and poor financial acumen; for all their naivete they have a stake in their destinies. The nuance is important. While it does not exonerate the Dutch it reframes a storyline allowing for a future that is expansive, neither cowed by the past nor beholden to it.