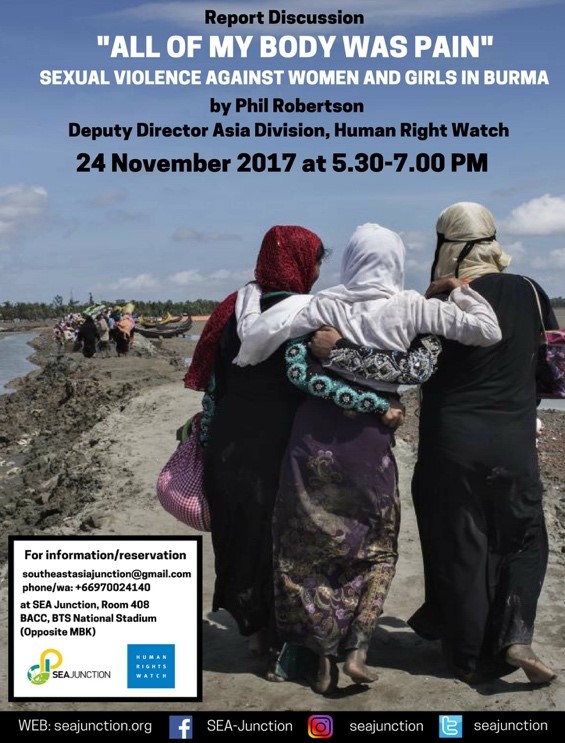

Presentation of Phil Robertson, Deputy Director, Asia Division, Human Rights Watch At SEA Junction, Bangkok Arts and Cultural Center, Bangkok, Thailand, November 24, 2017

Thank you all for being here. My name is Phil Robertson[1], and I’m the deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch. I want to thank you all for coming, and I want to thank SEA Junction’s director, Rosalia Sciortino, for inviting me to present this very important, and frankly, disturbing research about the serious atrocities committed by the Burma army against Rohingya women and girls in northern Rakhine state.

I’m here to talk about our recent report, “‘All of My Body Was Pain’: Sexual Violence Against Rohingya Women and Girls in Burma.”[2] HRW formally launched this report about a week ago, in New York. The researcher and author the report is Skye Wheeler, our emergencies researcher at our Women’s Rights Division, who has done extensive work on Sexual and Gender Based Violence in South Sudan, Burundi, and other parts of Africa and the world.[3]

Our research documents how Burmese security forces have committed widespread rape against women and girls as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims in Burma’s Rakhine State.

In preparing to give this presentation today, I have struggled to put into words the exceptional brutality that we documented, and the indescribable cruelty and humiliation that Rohingya women and girls were subjected to. I would also like to warn you that some of the accounts that I will share are quite disturbing.

As has been widely reported, since August 25, 2017, the Burmese military has committed killings, rapes, arbitrary arrests, and mass arson of homes in hundreds of predominantly Rohingya villages in northern Rakhine State, forcing more than 620,000 Rohingya to flee to neighboring Bangladesh. The humanitarian crisis caused by Burma’s atrocities against the Rohingya has been staggering in both scale and speed. This massive dislocation happened over weeks, not months – it’s been a tidal wave of people fleeing to Bangladesh.

The military operations were sparked by attacks by the armed group the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on 30 security force outposts and an army base that killed 11 Burmese security personnel. The Burmese military, supported by Border Police and armed ethnic Rakhine villagers, not only pursued those responsible, but immediately launched large-scale attacks against scores of Rohingya villages under the guise of counter-insurgency operations.

Human Rights Watch research has found that these abuses amount to crimes against humanity under international law.

Specifically, we found that the crimes against humanity include: a) forced population transfers and deportation, b) murder, c) rape and other sexual violence, and d) persecution as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the ad hoc international criminal courts.[4]

This report focuses primarily on the third of these crimes, the rape and sexual violence inflicted by Burma’s security forces on Rohingya women and girls.

In the first half of October, a Human Rights Watch researcher interviewed 52 Rohingya women and girls who had fled to Bangladesh, including 29 rape survivors. 3 of these rape survivors were girls under 18. We also spoke with 19 representatives of humanitarian organizations, United Nations agencies, and the Bangladeshi government. The rape survivors came from 19 villages in Rakhine State, mostly in northern Buthiduang and Maungdaw Townships.

Our reporting found a number of patterns about sexual violence against the Rohingya. These patterns include uniformed members of security forces as perpetrators, the high incidence of gang rapes, several instances of “mass rape,” and the patterns of sexual harassment and violence in the weeks leading up to attacks on villages.

Burmese soldiers raped women and girls both during major attacks on villages. In every case described to Human Rights Watch, the rapists were uniformed members of Burmese security forces, almost all military personnel. Those who were not Tatmadaw were from the Border Police. In some cases, Rakhine auxiliary groups or villagers also sexually harassed Rohingya women.

All but one of the rapes reported to Human Rights Watch were gang rapes. In eight cases women and girls reported being raped by five or more soldiers.

For instance, Fatima Begum, and that is not her real name, 33, was raped one day before she fled a major attack on her village during which dozens of people were massacred. She said:

I was held down by six men and raped by five of them. First, they [shot and] killed my brother … then they threw me to the side and one man tore my lungi [sarong], grabbed me by the mouth and held me still. He stuck a knife into my side and kept it there while the men were raping me, that was how they kept me in place. … I was trying to move and it was bleeding more. They were threatening to shoot me.

Fifteen-year-old Hala Sadak said that large areas of scarring on her right leg and knee were from where soldiers had stripped her naked and then dragged her from her home to a nearby tree where, she estimates, about 10 men raped her from behind. “They left me where I was,” Hala Sadak said. “When my brother and sister came to get me, I was lying there on the ground, they thought I was dead.”

The rapes were accompanied by further acts of violence, humiliation, and cruelty. Security forces beat women and girls with fists or guns, slapped them, bit their breasts, or kicked them with boots. Women reported that their attackers laughed at them during gang rapes or threatened them for by putting a gun to their heads. Some attackers also beat women’s children during the attacks.

Human Rights Watch document six reported instances of “mass rape.” In these cases, survivors said that soldiers gathered Rohingya women and girls into groups and then gang raped them.

Mamtaz Yunis said Burmese soldiers trapped her and about 20 other women for a night and two days without food or shelter on the side of a hill. She said the soldiers raped women in front of the gathered women, or took individual women away, and then returned the women, silent and ashamed, to the group. She told Human Rights Watch:

“The men in uniform, they were grabbing the women, pulling a lot of women, they pulled my clothes off and tore them off…. There were so many women … we were weeping but there was nothing we could do.”

Ethnic Rakhine villagers, acting alongside and in apparent coordination with government security forces, were also responsible for sexual harassment, often connected with looting.

What do we know about the scale of these abuses?

Humanitarian organizations working with refugees in Bangladesh have reported hundreds of rape cases. Between October 22 and 28 alone, 306 gender-based violence cases were reported, 96 percent of which included emergency medical care services.

But these most likely only represent a small proportion of the actual number. Ultimately, I think that we’re going to end up talking about at least hundreds of cases, and perhaps many more.

But I expect there will always been an underestimate of the numbers of affected women. The reasons for this include: a significant number of reported cases of victims who were raped and then killed and the deep stigma that makes victims reluctant to report sexual violence, especially in crowded emergency health clinics with little privacy. Two-thirds of rape survivors interviewed had not reported their rape to authorities or humanitarian organizations.

While the focus of our research was sexual violence, many of the women and girls that we interviewed also said that witnessing soldiers killing their family members was the most traumatic part of the attacks.

In 13 interviews, women or girls said they had seen soldiers murder close family members, including young children, their husbands, or elderly parents. One method was throwing older persons and young children into burning houses that they couldn’t escape.

Toyuba Yahya said seven men in military uniform raped her. She said that soldiers then killed two of her sons, ages 2 and 3 by beating their heads against the trunk of a tree outside her home. The soldiers then killed her 5-year-old daughter. She said: “My daughter, they picked her high up and then smashed her against the ground. She was killed. I do not know why they did that. [Now] I can’t eat, I can’t sleep. Instead: thoughts, thoughts, thoughts, thoughts. I can’t rest.”

For those who survived the attacks and were able to flee, the journey toward relative safety in Bangladesh was fraught with pain and hardship.

Gang-rape survivors reported days of agony walking with swollen and torn genitals through jungle to Bangladesh. “I just wanted to stop, I was so tired.… I cannot even tell you the pain of walking,” Hasina Begum said. For those who reached Bangladesh, many reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder or depression, and untreated injuries, including vaginal tears and bleeding, and infections.

None of the rape survivors we interviewed received post rape care in Burma. They missed access to urgent interventions that must take place within days of the rape, like emergency contraception (120 hours) and prophylaxis against HIV infection (72 hours).

The response by the Burmese authorities has been outrageous and shameful. They have rejected the growing documentation of sexual violence by the military, including previous Human Rights Watch reporting of widespread rape during military “clearance operations” in late 2016 in northern Rakhine State.

In September, the Rakhine state border security minister denied the reports, asking, “Where is the proof?” “Look at those women who are making these claims – would anyone want to rape them?” This has been a continuing, absolutely shameful narrative from leaders of the Burma army, disparaging Rohingya women while at the same time, doing nothing to constrain the soldiers from raping women of all ages.

In general, the government and military have failed to hold the military accountable for grave abuses, with the most recent example being a November 13 the report issued by a Burmese army “investigation team” that said there were “no deaths of innocent people” and denied any instances of rape or sexual violence. This report, produced by Defense Services Inspector General, Lt. Gen. Aye Win, is an absolute joke with no credibility at all. The report is a total whitewash of Tatmadaw atrocities – and yet another indication that Myanmar government or army cannot be allowed to investigate itself because there is no political will to do so.

In terms of broad recommendations from our report, I’ll just cover a few. Please download the report if you want to see them all.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of Burma to end human rights abuses against the Rohingya immediately, and to cooperate fully with international investigators, including the Fact-Finding Mission established by the UN Human Rights Council.

There should be an urgent effort to fully investigate the scope of sexual violence and other crimes against the Rohingya, and ensure that this information reaches those who can hold the perpetrators (and their commanders) accountable.

The international community, including donor governments, UN agencies and leaders, and others must press Burma to allow international humanitarian aid organizations to have unimpeded and unrestricted access to all parts of Rakhine State. Journalists and international rights monitors, like Human Rights Watch, should be allowed unobstructed access to areas where human rights violations, including rape and sexual violence, allegedly took place.

Bangladesh and international donors should act quickly to provide relief for the refugees, and expand assistance for rape survivors. There needs to be much more attention to the specific abuses suffered by Rohingya women and girls, including sexual violence, should be integrated into every aspect of the international response to this human rights and humanitarian crisis.

Donors, INGOs, UN agencies, and Bangladesh groups should help provide long-term post-rape care, including health care and psychosocial services. They should also create outreach programs to the Rohingya refugee community to reduce stigma around sexual violence and to inform individuals about available, free, and confidential medical and mental health services, including for post-rape care. Donors should introduce protocols so that health clinics and other facilities that treat women and girls who report rape provide them with a medical certificate for use in future investigations and prosecutions, while at the same time keeping certificate secure (perhaps at the clinic or health care facility) so that women do not suffer stigma by persons seeing the certificate at their residence.

We have to recognize there is a significant problem within the Rohingya community to accept women and girls who have been sexually violated, and understanding needs to be built, especially among Rohingya males, about this situation.

Importantly, while doing this research, we realized there is one reason, and reason only, why the women and girls were willing to speak to us, and relive the most horrible, traumatic moments of their lives at a moment when they are still coping with despair, uncertainty and loss. The reason is because they want justice. They want the international community to do more than wring its hands, they want them to act to hold their rapists, and their commanders, accountable.

For this reason, Human Rights Watch is also recommending that UN member states should impose travel bans and asset freezes on Burmese military officials implicated in human rights abuses; expand existing arms embargoes to include all military sales, assistance, and cooperation; and ban financial transactions with key Burmese military-owned enterprises.

Human Rights Watch calls on the UN Security Council (UNSC) to impose a full arms embargo on Burma and individual sanctions against military leaders responsible for grave violations of human rights, including sexual violence. Let’s return the Tatmadaw to the pariah status on the world stage that they occupied during the SLORC and SPDC military regimes in Burma.

We also think that the UN Security Council should refer the situation in Rakhine State to the International Criminal Court. This is because Burma has not yet ratified the Rome Statute, which established the court, meaning that only the UNSC can do what is needed – ad send Burma’s generals and their troops at long last to face justice for their crimes against the Rohingya women and girls.

To hear about the horrors that these women and girls have faced, the UNSC should request a briefing by the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Pramila Patten, who has just traveled to the camps in Bangladesh and conducted her own investigation of what happened to the Rohingya women and girls. Her findings are similar to ours.

In her end of mission statement, Patten said: “A clear picture is emerging of the alleged perpetrators of these atrocities and their modus operandi. Sexual violence is being commanded, orchestrated and perpetrated by the Armed Forces of Myanmar, otherwise known as the Tatmadaw. Other actors involved include the Myanmar Border Guard Police and militias composed of Rakhine Buddhists and other ethnic groups. Any actor that commits, commands or condones sexual violence against civilians must be held to account.”

“These brutal acts of sexual violence occurred in the context of collective persecution, the burning and footing of villages, torture, mutilation, and the slaughtering of civilians – even babies, who represent the next generation and the future of this community. The widespread threat and use of sexual violence was a driver and ‘push factor’ for forced displacement on a massive scale, and a calculated tool of terror aimed at the extermination and removal of the Rohingya as a group.”

Now more than 15 years since the report “License to Rape”[5] was first released about Tatmadaw rape and other abuses against Shan women and girls in eastern Burma, the army still operates with total impunity. It’s long past time for the world to bring this military, and its leaders, to justice for the many crimes they have committed against ethnic women and girls in areas all over the country. Unless they are stopped now, the Tatmadaw will certainly do it again.

Thank you, and I’m happy to answer your questions.

[1] Contact information: RobertP@hrw.org, mobile phone: +66-85-060-8406, Twitter: @Reaproy

[2] Full text available for free download at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/11/16/all-my-body-was-pain/sexual-violence-against-rohingya-women-and-girls-burma

[3] For more information: https://www.hrw.org/about/people/skye-wheeler

[4] For the full legal memo by Human Rights Watch, setting out the crimes committed in detail, please see: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/25/crimes-against-humanity-burmese-security-forces-against-rohingya-muslim-population

[5] Full text of report available for download: http://www.shanwomen.org/reports/36-license-to-rape