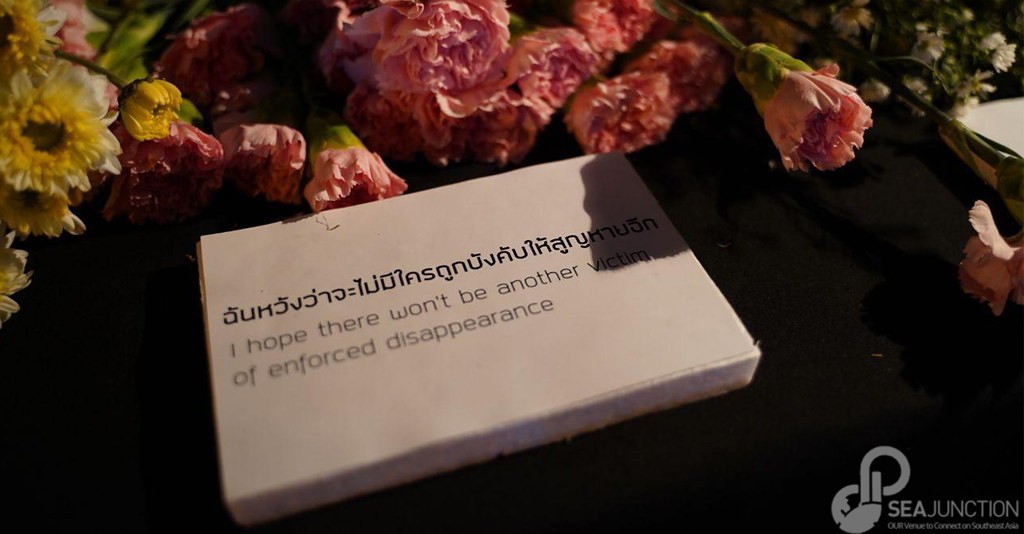

(Photo by Prachatai, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Article by Pornpen Khongkachonkiet originally published in Bangkok Post of 17 December 2021.

In June, the cabinet finally approved a draft of a landmark piece of legislation, the Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act. The law could go a long way toward ending some of the most egregious human rights abuses troubling our country.

Negotiations over the law in parliament have been marked by severe delays, and there are worrying signs that the government is trying to push through a watered-down version. This must not happen, as Thailand both deserves and badly needs a law that stamps out torture and disappearances once and for all.

It is indisputable that this law is necessary. In trying to push for it for over 14 years, civil society has recorded at least 30 “disappearances” in southern Thailand since 2004. Since 2014, another two cases of land activists and nine Thais living abroad have been added to the list. These include labour and land activists, lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. In 2020, democracy campaigner Wanchalearm Satsaksit was snatched in broad daylight on the streets of Phnom Penh.

Torture has long been rife in Thailand, whether it be counterinsurgency operations in the deep South or in police detention. In August, a video of police allegedly torturing a suspected drug dealer to death went viral, sparking public outrage.

Despite the urgency of the issue, however, progress on the law since it was approved by the cabinet has been worryingly slow.

In September, the House of Representatives approved a draft on its first reading, and established a committee (of which I am a member, representing civil society) to review the law before the second and third readings in the House.

The committee is essentially trying to merge four versions of the law — one proposed by the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and three others by political parties — into a single document.

Unfortunately, the version proposed by the MOJ and approved by the cabinet is deeply problematic. It fails to meet international human rights standards and contains many “loopholes” that would in effect allow torture to continue without consequences, and would do little to get to the truth of disappearances.

One key issue is that, in its current form, the MOJ draft would only give the police and the Department of Special Investigation (DSI) the power to investigate complaints of torture.

Since the police have historically been reluctant to do so, especially when the accused are police officers, it would be better to allow other bodies, such as prosecutors or other civilian officials, the ability to launch investigations.

The draft is also weak on command responsibility, and fails to adequately punish higher-ranking officers who do not do enough to prevent and investigate torture in their ranks.

It is worrying that the draft law makes no reference to “cruel and inhumane” treatment in addition to torture. This is a legal term that would cover a range of abuses inflicted on those held in Thailand’s overcrowded prisons or even students forced by their seniors to endure a hazing culture. There are also real concerns about the reliance on military courts to try torture cases.

In addition, the law proposes the establishment of an independent committee to monitor torture in Thailand. The current version, however, envisions a largely toothless body that does not have enough representation from civil society or forensic experts.

International human rights groups share many of these concerns. Amnesty International and the International Commission of Jurists have warned of “significant shortcomings” in the current draft, while highlighting “recurrent delays” in finalising the law.

Many of these issues are addressed in the other three versions of the law before the committee, but government representatives have been reluctant to accept changes. Despite having held 27 meetings since September, the committee remains deadlocked.

There is a fear that we will end up with a version of the law that is little more than a paper promise to end torture. Or even worse, that we will end up with no law at all.

Time is not on our side, as the parliamentary session ends in February. There is also a chance that parliament could be dissolved next year ahead of the next general election that must take place before March 2023. If the dissolution happens before the bill is passed, we will have no option but to start over again when a new government is in place.

Passing the Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Act must be a priority. The government must ensure that the final version of the law provides genuine protection against these heinous crimes, and that perpetrators be held to account.

The people of Thailand, and the many torture victims and their families, deserve much better than a paper promise.

Pornpen Khongkachonkiet is director of the Cross Cultural Foundation.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/2233319/bury-at-sea-any-watered-down-torture-law