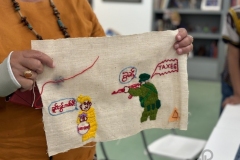

Renowned artist Jakkai Siributr’s new long-term project, There’s No Place is a collaborative ‘call-and response’ embroidery piece that creates an ongoing dialogue between the displaced ethnic Shan communities of Thailand—notably that of Koung Jor Shan Refugee Camp (KJSRC) and those served by Shan Youth Power—and viewers around the world. KJSRC is an unofficial camp on temple land that was established in 2002 when about 500 refugees fleeing from fighting between the Shan State Army-South and government troops arrived in Thailand. Many have called the camp home for almost two decades, and a new generation born within its boundaries, has known no other home and remain effectively stateless. Education and livelihood initiatives can help refugees thrive, retain dignity, contribute to the economy of their host country. But unable to partake in the formal workforce, Siributr invites the residents of the KJSRC to become his primary collaborators in this project, offering them work within the perimeters of the camp, and compensating them with daily wages. Siributr’s collaborators are now embroidering their stories—how they came to be there; their ideas of home; their hopes, and their fears.

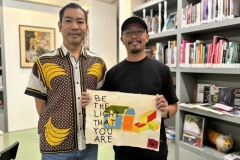

Building upon the artist’s earlier work on displacement, There’s No Place is a participatory project exploring identity, belonging, and ‘home,’ inspired by a personal attempt to reckon with the protracted refugee situation on the Thai-Burma border. Following a series of interactive sessions in various locations, on 17 August there was an opportunity for the public to meet Siributr and contributed to this project during two sessions which were held at SEA Junction at 10-12am (1st session) and at 1.30-3.30pm (2nd session). A maximum of 20 participants per session embroidered on the same piece of cloth that has been previously embroidered by the Shan community.

This work aims to explore the conditions of refugeehood in a way that goes beyond the vocabulary of aid, help, and development: By unearthing how we ourselves are heirs to the stories of refugees, this work becomes a meaningful way to indict today’s neglect. The project also looks at the audience—not as a passive receiver of predefined content—but as an active member of a constituent body, whom the textile provokes and inspires. Through this, and through his own embroideries that are interspersed throughout the final textile as a connective tissue, the artist is addressing issues such as ownership and power dynamics, collaboration, and economies of exchange. There is implicit here, an expressed urgency to move away from the usual binary used to describe refugees, migrants, and the host country: that one either lives a temporary life in a refugee camp, or that one becomes a citizen with a permanent residency. In reality, there’s a huge spectrum between those two binaries.

Photo credits: Chawin Chantalikit and SEA Junction’s Team