“We had no time for ourselves, for our needs…. not even for coffee. We would put granules of instant coffee into our mouths and wash it down with water so that we could go on working. If the captain or any of the supervisors felt that we were not working hard enough we were whipped or beaten with sting ray tails or rope ends.”

“We had no time for ourselves, for our needs…. not even for coffee. We would put granules of instant coffee into our mouths and wash it down with water so that we could go on working. If the captain or any of the supervisors felt that we were not working hard enough we were whipped or beaten with sting ray tails or rope ends.”

This was a part of the testimony given by Samat, a Cambodian who was trafficked by a ‘broker’ and worked on a Thai fishing trawler, more or less a slave, for more than five years without setting foot on land before he escaped.

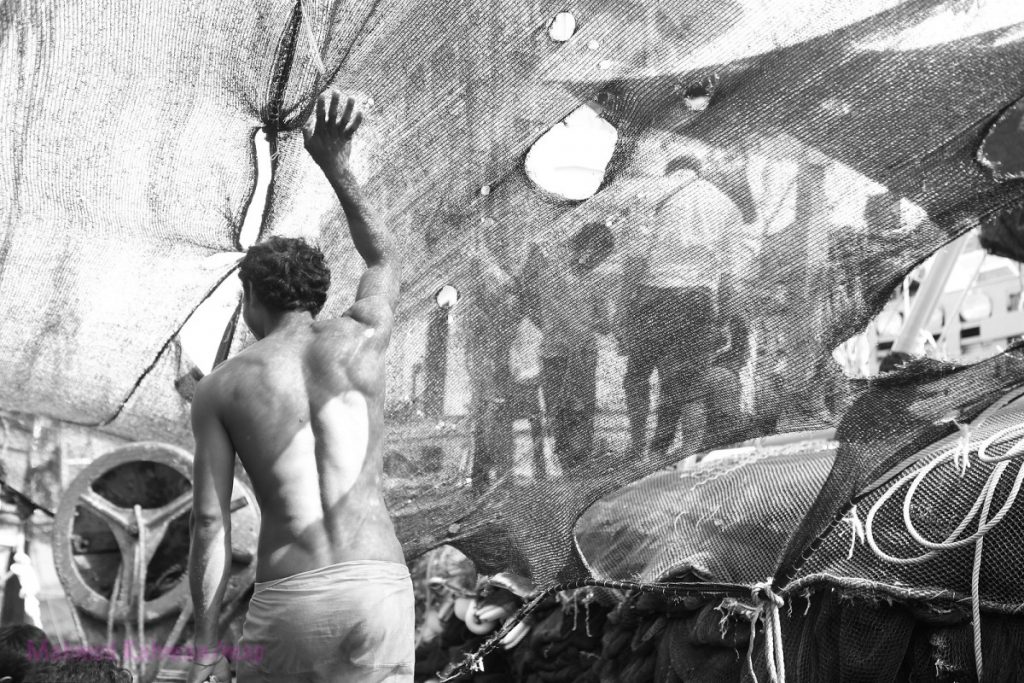

The occasion was an exhibition of photographs at the SEA Junction (‘South East Asia’ Junction) by Mahmud Rahman, a Bangladeshi professional photographer, and I had the privilege of being invited to the opening event. Through these photographs, Mahmud sought to document, highlight and create awareness of the plight of migrant laborers from Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam to Thailand and Indonesia. Mostly males, these migrants were trafficked into working under conditions of near slavery within the Thai and Indonesian fishing industry. The main markets for the processed seafood from this industry are in Europe and the USA.

Mahmud spent almost two years studying the Thai fishing industry, working his way south along the coast from Bangkok, mostly on his bicycle and spending time, sometimes days, living in these with fisher communities in the various ‘piers’, the coastal enclaves that the fishing boats departed from. He was able to make it all the way to Pattani in the ‘deep south’.

Mahmud is passionate about understanding and through his photography documenting the socio-cultural aspects of indigenous peoples and those who survive on marginal livelihoods and physical labour. This passion often led to the commissioning of work as a professional photographer by institutions and their causes. For me what stood out and was special about Mahmud’s photography was the ability of his work to invoke empathy and the creation of an emotional link with his subjects.

While Mahmud was not able to spend time on the boats on fishing runs he was able to spend time in the fishing villages and interact with the families and women folk of the Thai fishermen.

The SEA Junction, located within the very impressive and modernistic Bangkok Arts and Cultural Centre (BACC) in Bangkok, Thailand functions as resource centre whose stated aspiration is to ‘foster understanding and appreciation of south east Asia in all its realities and socio-cultural dimensions’. It primarily serves as a documentary resource centre and a reading area but also actively promotes discussion and dialogue on issues related to South East Asia.

Mahmud’s curated exhibition included a discussion led by a panel add up of the CEO of the Labour Rights Promotion Network (LPN) which is a nonprofit organisation committed to ensuring the right of migrant labourers, the Deputy Director for Human Rights Watch (HRW) in Asia and Mahmud.

The discussion was followed by testimony from two migrants from Cambodia and Myanmar (Burma) who had managed to escape, which were heart breaking to listen to.

“Most of the work was to cast the nets and draw them in which took about four hours, and we did this around five to six times a day. Sometimes we went two to three days without sleep and time to eat or rest. We were constantly beaten and abused by our overseers. We could not see properly due to exhaustion and our eyes were blurry. Very often we injured ourselves. The worst work was packing the fish into 25 — 30 kg. blocks and stacking them manually in the freezer holds. The cold and the stench were unbearable ”.

The migrant from Myanmar raised up his hand which was missing four fingers and consisted only of the thumb and a part of the palm when he injured himself while working. “I was not taken ashore or given any medical treatment for more than a month and constantly kept my hand on ice to staunch the bleeding and reduce the pain. There was an instance when a Burmese migrant jumped over the side of the boat in desperation thinking that he could swim his way to the shore, but he got entangled in the net and drowned. His corpse was thrown into the sea”.

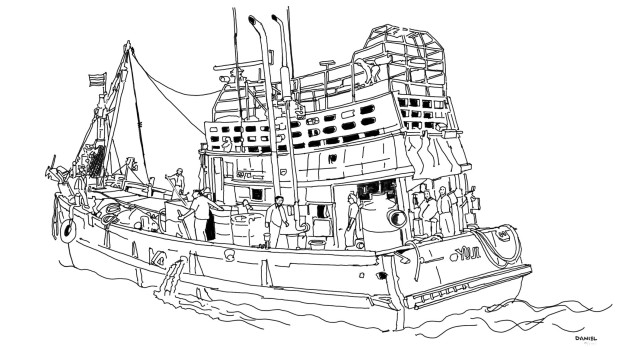

When the fishing boats and trawlers returned to land after three to four weeks of fishing they transferred the migrant workers to boats that were outbound on their way out at mid-sea. These transfers ensured that the migrants would not be able to set foot on land, resulting in their time on these boats measured in years.

The situation of these migrants working under conditions of near slavery within the industry was not new but came into prominence as serious violations of human rights following exposes by prominent news agencies such as the Associated Press, The Guardian and the New York Times. These ‘specials’ in editorials and supplements of these newspapers paint a picture of such stark misery, deprivation and sadistic abuse that is almost impossible to imagine and comprehend that such conditions could actually exist in these times.

Following these exposes and the work of organisations such as LPN, HRW supported by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and regulatory measures put in place by the governments of Indonesia and Thailand the industry, described as a ‘a lawless country of its own within our world’, the industry and practices have improved. The EU has also cooperated by ‘yellow carding’ supermarket chains in Europe that did not have adequate measures of due diligence in place to monitor compliances with regard to sourcing and processing.

But the industry has adapted by moving further across the oceans to places like Madagascar and the African coast where poverty and misery can still be exploited without consequences.

So, the next time you pick up a tin of seafood on your supermarket chain that says ‘Processed in xxxxx’, give a thought to the amount of misery and the corrosive exploitation that could have gone into producing its contents.

January 29, 2017, Bangkok, Thailand

For more of Mahmud’s photography check out his posts on Instagram (Profile: mahmudphotodhaka) and Facebook

Note: The photographs in this post are the intellectual property of Mahmud Rahman. The photographs may be used for non-commercial purposes with attribution to source.

Source : https://danielsinnathamby.com/2017/02/03/sea-junction/