Globally, trade in fish products continues to reach record highs and Thailand has emerged as a major supplier, with the value of its seafood exports reaching US$6 billion in recent years. And a significant contribution to the industry’s growth is made by the migrant labour force. The new photo exhibition displaying their “voices” through the photographs they took invites you to look into their human sides.

Shortages of Thai workers willing to work on fishing vessels, emerging simultaneously with expanding structural differences in population demographics and economic development between Thailand and its neighbouring countries, have transformed fishing crews to predominantly consist of migrant workers from Cambodia and Myanmar. Several hundred thousand women and men migrant workers are now employed at different levels within the seafood supply chain in Thailand, working precariously under various temporary labour migration regimes and constrained living and work conditions

Recognizing the contribution of migrant workers to Thailand’s society and the blue economy, the exhibition, Not Just Labor; Migrant Photo Voices from Thailand’s Fisheries, gives them a platform to showcase their “photo voices”. The display consists of photos taken on their mobile phone by migrants from Cambodia and Myanmar, who are now living in Phuket, Phang Nga, and Chanthaburi to work in the fishing and seafood industry.

They highlight the often-overlooked aspect of migration as an experience that transcends work by capturing their overall day-to-day existence full of taxing, entertaining or simply mundane events, of interaction with their natural and social surroundings, and of dreams and expectations about the future.

The message these photo voices (and the exhibition’s title) convey, is that migrants are more than just labour and more than the sum of the difficulties and exploitation endured. Moreover, the photos also show how migrants’ lives have become interconnected with the larger Thai society, pointing to the need to introduce integration policies.

Against the dehumanised portrayal of migrants as faceless ‘others’, this exhibition celebrates their identity, agency, personality and other features of our shared humanity. This comprehensive appreciation of migrants’ experiences and aspirations, is essential to create an inclusive and more equitable society that upholds everyone’s human dignity.

The exhibition, organized and curated by SEA Junction with support of the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s Ship to Shore Rights South East Asia initiative funded by the European Union, will be on display from May 14 to 26, 11am to 7pm, at the Curved Wall, 4th floor of BACC.

Pyae Sone Aung

“I am 18 years old. My mother has been in Thailand for 30 years now. I tried to go to Malaysia to find a job but was caught as I had no documents and spent 9 months in prison before being sent back to Myanmar. In Myanmar, I worked in the aluminium windows and doors factory since I was 16 years old.

“I have been in Thailand for almost a year now. A month ago, I started working on a black trawler boat. The views from the boat are astonishing and I wish others could see the scenery. When I was free on the boat, I quickly took a snapshot on the phone and immediately posted it on Facebook for people to enjoy.”

Ngeth Sarath

“I am a worker from Kampot. I am 43 years old and have lived in Thailand for about 20 years. I am a squid fisher, and sometimes I have to sail offshore for more than 10 days. My wife is from Prey Veng. We met in Thailand and now have two 8-year-old twin children, one lives in Kampot and one lives here. We rarely reunite as it takes a fortune for us to travel to Kampot.

“In Cambodia, we never had New Year parties because we only celebrate Songkran, so we enjoy doing it here. The photos are from the 2024 New Year party that we organized in the market with the other 40-50 Cambodian workers living in Laem Sing district. We held a fancy costume competition, with a 1st prize of 500 baht and a 2nd prize of 300 baht. The 1st prize winner was a construction worker. There was also a raffle, with gifts of at least 200 baht such as dishes, bed sheets, toiletries, and money. People were delighted to receive fans and rice but didn’t want the dishes and cups since they had them.

“A Cambodian monk from a forest temple also came and blessed us. A few Burmese migrants also participated. One of them has stayed here for a long time. He speaks Thai and Khmer and has a Cambodian wife. There are fewer fishing vessels right now, so Burmese people went to seek for jobs in Mahachai. In the past, there were only Myanmar people in the area, but now only Cambodians come here. There were almost 100 Cambodian migrants at the party coming from Rayong, Koh Proet and Bangkok. During the pandemic, we could not do anything, but this year we were all smiles, so I took the photos to remember this happy moment.”

Bo Chanda

“I live in Ko Proet, Chanthaburi. In 2008, I worked in the mangosteen industry, but now I work as a shrimp sorter. My photo story narrates the wedding of my neighbour and friend, a Cambodian worker, who I have known since he was a child, with his Thai girlfriend who comes from Khao Luk Chang (Baby Elephant Mountain).

“The groom was born in Thailand and has been living with his parents. His father, who used to sail the boat offshore, has been in Thailand for more than 30 years. He now works on a shrimp farm, while his mother works as a domestic worker. My friend met the bride who is a mangosteen and durian farmer and moved to the farm to help her. However, he doesn’t have Thai citizenship, which is very difficult to apply for.

“For the wedding, we all dressed in pink according to the wishes of the groom. Since I came to Thailand with a small case, I bought the dress online, since the elegant Cambodian dresses available here for rent were too expensive. The groom’s mother rented the whole bus for our group to go together. We partied on the bus for almost two hours, drinking alcohol and dancing. People at the wedding party came from different places as Cambodian workers like to gather at weddings and other festive occasions. We have networks connecting us in Thailand.”

Som Rong

“I am Som Rong, a 34-year-old Cambodian migrant worker. Here I talk about my friend’s funeral, She was also a migrant working in the fishing industry. When she got sick, she moved to her mother’s room. We believe she got sick from the chemical used in the Longan plantation in Rayong where she worked before. Migrants who die in Thailand face a tragic fate because their relatives cannot attend the funeral, since they have no passports, and it is expensive. So, we just tell the relatives the sad news and they make merit in Cambodia.

“We organized the funeral in the Thai way, which is similar to our way. After the cremation, we cannot bring her ashes to the rental room as the owner is a good guy, but he is very superstitious. We put her ashes in an urn under the temple’s tree. The mother would like to bring the urn to Cambodia, but she is not sure if she can go, so she may give it to friends or other relatives to carry when they go back to Songkran. Not all migrant workers can or dare to bring the remains of the deceased back, most would just scatter the ashes in the sea.

“The funeral only lasted one night to minimize the expenses and we cremated her the next day. There was also a tie-cutting ceremony, separating her from her husband and unleashing her from this world like we do in Cambodia. The owner of the squid vessel for whom she had worked for a long time also came to attend the funeral. He also cared for her when she fell sick in Rayong during COVID-19. Her husband is now working for him. The chair of the fishing association of Chanthaburi also attended the funeral. Migrant friends helped cover the costs of her funeral.”

Ngu War Phoo

“I am now 25 years old, and I came to Thailand from Dawei when I was 18. When I first came to Phuket, I worked in a grocery store. Unfortunately, since I had no work permit, I was forced out of the job and had to look for other opportunities. I worked in a factory, a restaurant, and then in a tuna factory. I now work as a crab carver and a housemaid in Phuket.

“Crab carving is very important for the seafood industry in the province. I want to tell the story of my daily life making a living by carving crab skin. Starting from collecting the crab from the business owner’s house, then carving the crab at my home and throwing the shells away. The jumbo lump can be sold for 70 baht per kilogram.

“But the small ones can be sold for 100 baht per kilogram, as they are more difficult to carve. Someday, I can make 7 kilograms at maximum. Some other days, if we caught fewer crabs, I could only make 2 kilograms. Without crabs, there is no work, and no wages. In that case, I work as a housemaid. My boyfriend works as a fisherman and is often on the boat out at sea. We have one child.”

Ma Yu Yu

“I am from Dawei and I am now 40 years old. I have been in Thailand for more than 10 years, mostly in Phuket. Before COVID-19 I could travel to Dawei, but now it is difficult. I used to carve the crab before recently quitting the job to become a housemaid. Carving crab was very tiring, as it required concentration and I had to sit all day long. It hurt my legs and knees.

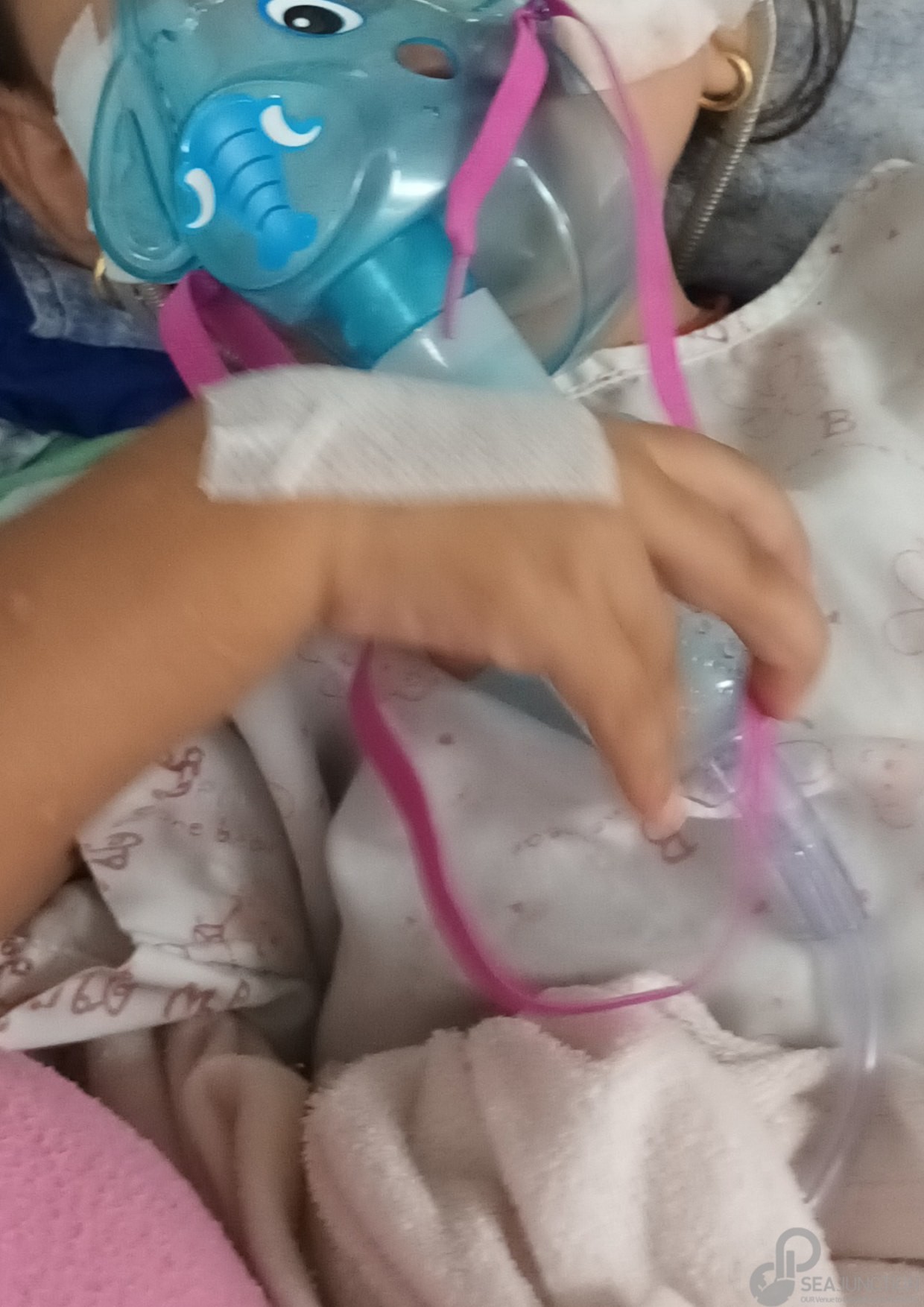

“I have a son and two daughters. The girl in the picture is my youngest. She has been suffering from heart valve regurgitation since birth. The hospital where she was born rejected the case, citing her serious medical condition and because we do not have money or insurance and treatment is very costly. Luckily, a non-governmental organization helped us get a migrant health card. That is how she continues to receive the treatment and is able to live a normal life. Now, she is 3 years old and still needs to go to the doctor regularly.”

Source : https://bkktribune.com/not-just-labor-migrant-photo-voices-from-thailands-fisheries-part-i/