Message from Patrick Mccormick: “Digitized Mon-Language Manuscripts now online!”

I am pleased to announce that a collection of nearly one thousand Mon-language manuscripts have been digitized and placed online, where they are searchable, accessible, and can be downloaded for free. Funding from the Endangered Archives Programme, run through the British Library, under the title “Recalling a Translocal Past: Digitizing Mon Palm-Leaf Manuscripts of Thailand, Part 2”, made this project possible.

Link: https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP1432

I want to express my gratitude to SEA Junction https://seajunction.org/ and the Thai Studies Center at Chulalongkorn University for their invaluable help in making this project possible; to all the members of the Thai Mon and Burma Mon communities, including but not limited to Nai Sunthorn, Mi Budsaba and Daw Pyone Pyone Aye for their help, patience and guidance; the abbots at Wat Koh, Wat Saladaeng Neua, Wat Pom and Wat Khongkharam for their permission; the project driver Phi Tu (Kittimase Thitanopphan) and project photographer Phi Tae (Akanan Titanoppun); and finally Dr. Jennifer Wong for her computer expertise.

Materials:

Materials:

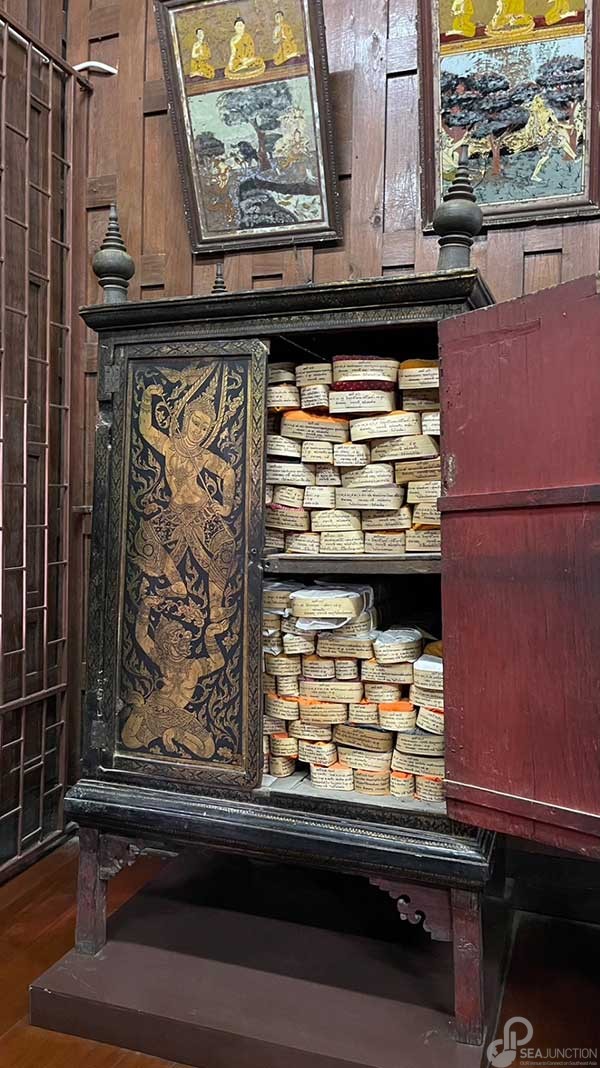

Texts date from the mid-nineteenth through to early twentieth centuries, with a few dating as early as the late eighteenth century and others the 1940s. The bulk are palm leaf manuscripts written in the Mon script, both in the Mon language and in Pāli, with a substantial number also of parabaik or samut khoi “accordion” books written on paper, many of which are beautifully illustrated. Thai-and Pāli-language manuscripts, written in the Khom script—a variant of Khmer—have also been included.

Subjects include didactic texts, commentaries, monastic discipline, ordination, meditation, and the Abhidhamma among others. Also included are bilingual Pāli-Mon nissaya or trāy texts, vocabularies, and interlinear glossed texts. Significantly, this collection also covers large numbers of “secular” topics, such as works of literature, astrology and divination, customs, music, medical treatment (especially well represented in the parabaik), and history.

Background:

The “Thai Mon” or Thai Rāman community finds its origins in waves of migrations from the Mon-speaking areas of Lower Burma to Central and Northern Thailand, from the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries. These migrants built their own villages, where they maintained their language and culture well into the twentieth century. Manuscripts were central to monastic life and education for the saṅgha and laity alike. The Thai Mon community created and preserved thousands of manuscripts, which have been kept through to the present in around thirty to forty historically Mon temples, mostly in Central Thailand.

Today, however, the Thai Mon community has become highly assimilated to mainstream Thai culture. From above, changes in Thai law starting in the 1940s, and the extension of state control over monastic life, radically shifted the status of the Mon language and Mon language education. Only the standard Central Thai language and script were allowed in education, which was effectively shifted out of monastic schools and into government schools. From below, the proximity to Bangkok of so many Thai Mon communities and the opportunities available in the Thai language drew people to gradually shift to Thai as their primary language. Mon first became a primarily oral language until becoming moribund, with only elderly people in rural communities using the language regularly today. Very few Thai Mons are literate in their heritage language today, and of those, only vanishingly few literate to the degree that they can read these manuscripts. (In Burma, of course, substantial numbers of Mon people are literate in the language and able to read such manuscripts).

Significance:

Significance:

The significance of this project is threefold.

First, this is the largest cache of Mon-language materials to be put online, and thus represents a major development for the scholarship of Mainland Southeast Asia. Scholars of history and Buddhism make frequent reference to so-called “Mon sources” yet generally have not read them. Now a host of texts are available to the scholarly community and to the Mon community itself.

Second, a significant number of the digitized texts are unknown inside of Burma, where palm-leaf manuscripts have been well documented since the 1930s. Additionally, this is first cache of Khom manuscripts to have ever been digitized, as far as is known.

Third, the project represents the first large-scale of Mon materials using high-quality equipment and processing, and which have been made available online. We recognize previous efforts, but because of the funding and technology of the time, the results were not of this quality, nor were they made available online. Unlike other similar projects, the British Library does not treat these materials as the patrimoine culturel of the Mons or of Thailand, and so does not restrict access in any way.

Patrick McCormick, Bangkok September 2024