Executive report of panel discussion by Catharina Maria [1] and Rosalia Sciortino [2]

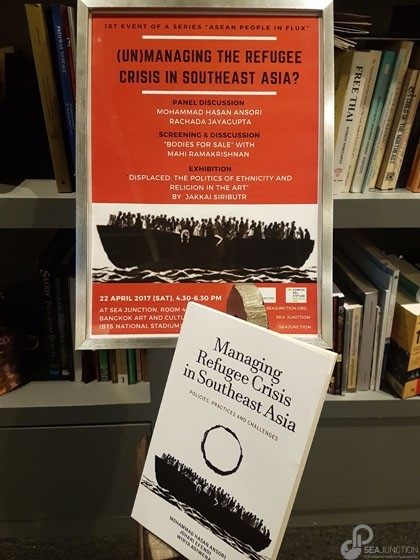

ASEAN member states struggle to find effective solutions when confronted with forced movements of people escaping conflict and seeking refuge across border. A clear illustration of this lack of sustainable and humanitarian approaches has been the regional response to the Rohingya crisis. Hundreds of thousands ethnic Rohingya have tried to escape systemic violence and persecution in Myanmar. In 2015 many were stranded at sea in rickety boats while seeking refuge in other Southeast Asian countries, and it took time –and human lives– before Malaysia and Indonesia agreed to provide some shelter in temporary refugee camps. Thus, the title of our event “(Un)Managing the Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia?” that was conducted at SEA Junction, at the Bangkok Arts and Culture Center (BACC), in collaboration the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southeast Asia. The title also refers to the content of the event centered on discussion of the book Managing Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia written by Mohamad Hasan Ansori, Johan Efendi and Wirya Adiwena and recently published in Indonesia.

ASEAN member states struggle to find effective solutions when confronted with forced movements of people escaping conflict and seeking refuge across border. A clear illustration of this lack of sustainable and humanitarian approaches has been the regional response to the Rohingya crisis. Hundreds of thousands ethnic Rohingya have tried to escape systemic violence and persecution in Myanmar. In 2015 many were stranded at sea in rickety boats while seeking refuge in other Southeast Asian countries, and it took time –and human lives– before Malaysia and Indonesia agreed to provide some shelter in temporary refugee camps. Thus, the title of our event “(Un)Managing the Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia?” that was conducted at SEA Junction, at the Bangkok Arts and Culture Center (BACC), in collaboration the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southeast Asia. The title also refers to the content of the event centered on discussion of the book Managing Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia written by Mohamad Hasan Ansori, Johan Efendi and Wirya Adiwena and recently published in Indonesia.

Rosalia (Lia) Sciortino Sumaryono, the Founder and Executive Director of SEA Junction and Associate Professor, Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University opened this event by welcoming the speakers and participants. She then briefly explained that this was the first of a series of events on movements of people in Southeast Asia entitled ASEAN People in Flux, which is organized by SEA Junction in collaboration with the Heinrich Boll Stiftung Southeast Asia. The aim of the series is to better understand the rise in intraregional mobility linked to regionalization efforts and examining the policies governing them. In particular, by putting a spot on different kinds of people movements, the series consisting of seven interrelated events highlights the double standards in ASEAN approach. On one side, ASEAN promotes “people to people connectivity” by facilitating movements for business, study and tourism, while on the other side it limits migration of much needed “un-skilled” workers to exploitative contract labor schemes and it refuses to recognize refugees, asylum seekers and displaced persons.

The event consisted of three parts: 1) a screening and discussion of the documentary Bodies for Sales with filmmaker Mahi Ramakrishnan; 2) a panel discussion with Mohammad Hasan Ansori the leading author of the Managing Refugee Crisis in Southeast Asia study and Team Leader of Humanitarian Refugee Program at the Habibie Center in Jakarta, Indonesia, and migration expert at the Asian Research Center for Migration (ARCM) of Chulalongkorn University, Rachada Jayagupta; and 3) a visit lead by the artist Jakkai Siributr to his exhibition DISPLACED: The Politics of Ethnicity and Religion in the Art in the same floor of SEA Junction at BACC.

The movie Bodies for Sale is a short investigative documentary that focuses on the role of traffickers, who become abusers, while facilitating refugees’ escape. It shows the suffering the Rohingyas have to endure at the hand of traffickers in their desperate attempt to find safety in Malaysia or other countries. Girls and women, but also at times men, become victim of sexual violence and rape, as a 20-second-footage tragically shows. Later, during the question and answer session, the director, Mahi Ramakrishnan, discussed the process of making the film and the time devoted to establishing contacts to gain access to the trafficker networks. She told the audience that it took years to complete the half-hour documentary and that it was very difficult emotionally to feel the survivors’ trauma and horrifying experiences. Mahi hoped that by showing the heinous realities that the Rohingyas faced, will make the public and policy makers empathize with their plights and be more willing to integrate them into society. She stressed the vulnerability of the Rohingyas in Malaysia, as even those who have a UNCHR card are exposed to arrest and detention any time. CSOs and NGOs do work in the shadow of the law to help refugee survive and make a living in the country, but they too have to be careful as they are considered illegal in providing services to the Rohingyas.

After watching the documentary, a moved audience listened carefully to the panel presentations. Hasan Ansori provided a context to the suffering of the Rohingya by presenting the findings of the Habibie Center research in Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia published in the book he co-authored. These countries are facing the influx of refugees who escape prosecutions and hope to live there or transit to Australia, Canada, New Zealand or Europe. One-third of refugees in Southeast Asia are hosted in Malaysia, 20% in Thailand, and a smaller number in Indonesia, Cambodia and Philippines. In Southeast Asia, only Timor-Leste, the Philippines and Cambodia are signatories to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol as countries fear that signing them will become a pull factor for refugees to come. As a result, any policies and practices that do emerge are short-term and ad-hoc and lacking enforcement mechanisms. Moreover, they are meant to endorse the national interests, particularly in terms of domestic security, rather than prioritize the rights and well-being of refugees. Thailand and Indonesia provide no access to health and education services, although now some refugees can access jobs in Thailand as a pilot. Unlike those coming from other countries, Rohingya refugees do not receive basic education and basic services in Malaysia. Malaysia created work permit pilot project for 300 Rohingya refugees, but only 45 signed up as the jobs were only at plantations where the abuse mostly happened. While their presence is tolerated, the lack of formal protection put refugees in a vulnerable position. At the same time ASEAN principles of non-interference and consensus stand in the way of putting pressure on Myanmar to stop persecution of the Rohingya people, if not through informal, non-public channels.

Rachada Jayagupta explained in more details the situation in Thailand. Most often Thailand is a transit country for the Rohingya refugees on their way to Malaysia or other third countries. Some, however, decide to stay or come back from Malaysia if disappointed. They frequently become victims of trafficking and corruption and their conditions are also impacted by the ever-changing political cycles – military rule, new constitution, election, conflict and back to military rule. As Thailand has not signed the international refugee agrements, Rohingyas are considered victims of trafficking. This implies that they will be placed in temporary shelters, waiting for repatriation eventually. There they experience cultural differences, language barriers and limited freedom of movements, while there is no clarity about resettlement and a future for their kids. Efforts are being made to address some of these concerns and also the special needs of girls and women staying at the shelters, using the national mechanisms in place for gender-based protection involving the UN and NGOs. Still, refugees often run away from the shelters, as they want to be free, work, be reunited with their families and have a better life.

Julia Mayerhofer from the Asia-Pacific Refugee Rights Network, who was in the audience was asked to open the discussion. She reiterated that based on the experience of the more of 300 member organizations in the Network, there is gap of solutions offered, whihc is only partially filled by civil society groups and international organizations. The refugee situation is dire, while voluntary return is not an option – especially for Rohingyas as conditions in Myanmar are not safe. The Governments of Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia are reluctant to move forward with local reintegration. They provide no legal recognition so refugees live and work under the radar. Only a tiny fraction of the refugees will be resettled, especially with the US and Australia reducing their intake, so more refugees are stuck in a legal limbo.

The discussion then explored what could be done in such a restrictive environment. Approaches mentioned by the speakers and their values in initiating more sustainable programs and policies were discussed. As a change of direction in terms of subscribing to international refugees conventions does not seem realistic, some suggested to work with existing mechanisms, such as ASEAN mechanisms to combat human trafficking through regional cooperation or refer to Sustainable Development Goal 16 on how to build peace, justice and strong institution. Others felt, that those frameworks would not be sufficient as they have too many shortcomings when they are applied to people who have no options of returning to their country of origin and that ratification of the refugee convention should still be advocated as a pre-condition for refugee protections. For Malaysia, NGOs should capitalize on the Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak’s strong stand on the Rohingyas by pushing for the ratification of Convention and for him to convince other leaders to put pressure on Myanmar. If not at the regional and international level, at the national level there may be space for innovations that can then be diffused regionally. Many stressed the importance of documenting and encouraging continuation and duplication of good practices like the work permit for refugees in Malaysia, and the presidential decree to support refugees in Indonesia. Key to any approach is to involve the public. When Rohingya boats were stranded in Indonesia, the Acehnese people were the one who took the initiative to help them as fellow human being. At the same time, citizens may be opposed to fully integrate refugees in their society as they have many prejudices against them and may feel new inhabitants may put a strain on services and public resources. Public education and cultural exchanges are important to enhance mutual understanding and build bridges among the refugees and the local population.

The potential of the arts to address challenging issues and communicate them to the public was evident in the exhibition Displaced and curated by Iola Lenzi. The artist Jakkai Siributr was there to explain about his arts installations on the politics of ethnicity and religion in Thailand and Southeast Asia. Two of the installations focused on the conflict in Southern Thailand, while the third one entitled “The Outlaw’s Flag” explored the Rohingya status of being without a nation via a video and a flag installation of 21 invented “flags” with embodied textiles and beads from Myanmar. Through his work, the artist challenges ideas of nationalism and its setting of boundaries that create exclusion, persecution and displacement. May enhanced public awareness serve to improve the lives of refugees in the region and beyond.

[1] Catharina Maria, independent consultant with expertise in peace building, gender, and capacity building

[2] Rosalia Sciortino is the Founder and Executive Director of SEA Junction (seajunction.org) and Associate Professor, Institute for Population and Social Research (IPSR), Mahidol University (www.ipsr.mahidol.ac.th/).