| Title | “Living the Malindo Ways: The Mobility of Hopes and the Ghost of Development” |

| Author | Yuniardo Muhammed Alvarres |

Honorable Mentions: “Living the Malindo Ways: The Mobility of Hopes and the Ghost of Development” by Yuniardo Muhammed Alvarres

“I just met your dad after we both were already old. Everyone left the village when you were a child…”

Said my uncle during my first meeting with him in Kuala Lumpur. He left his house in Indonesia and became a migrant worker for fifteen years in Malaysia. Malindo (Malaysia Indonesia) is what they call the migration route between both countries. He, with more than a thousand people, is a pivotal part of Southeast Asia’s economic and infrastructure development. It also became a trigger for the development in the origin area of migrant workers, but this movement was not able to solve the problem that made them migrate. Even it makes the real problem become a ghost.

An Indonesian migrant worker standing in front of her house in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

a house of the migrant worker is under construction in the middle of rice field in East Java, Indonesia

an Indonesia migrant worker at her house she built in Indonesia. She will go back to become migrants worker to finish the house

The road that the migrants took is a road full of hope. The hope of success and the hope of having a better life in the future, become a reason why they are going to migrate,but the problem is when migration becomes the only option for them to realize their dreams.

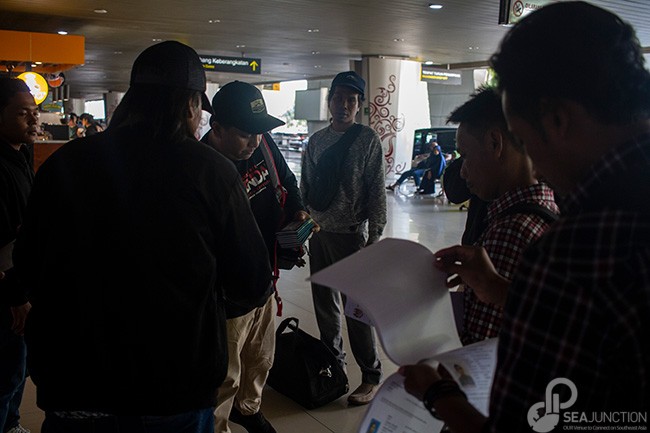

Group of migrants get a quick briefing with the agent at the airport before their departure

In most of rural East Java, the people rely on agriculture as their economic income. Eventually, the system doesn’t stand on the side of local farmers. They become very vulnerable and easily trapped in structural poverty.The rise of fertilizer costs, loss of new workforce, and the rising of land price caused by an increase of purchasing power by the migrant workers create force migration loops. The people told me that the household that doesn’t migrate can’t buy land because the successful migrant buys the land above the market price. The demand for land has become higher since the migration boom.

Worker migration is not a success guarantee activity. One of the ex-migrants I met explained that becoming a migrant worker is like spinning a wheel of fortune. This statement is interesting because it tells how much the migrants actually can take control of their lives.

From the departure airport, an agent already waits for them to give them the document. On the arrival airport, they need to go to the special line while waiting for people from the company that recruited them to pick them up. The bitter story of migrant workers doesn’t stop the mobility. Migration is still seen as a way to fulfill their dreams.

first sight of Malaysia from the plane that migrants took

the migrant worker in Malaysia video calling with his wife and mother- in law

high ceiling on the migrant house. The host want to build two-story house but miscalculated the cost

unfinished migrant house. The window and door is less important part of the house. They usually put it as a last part of building house. The migrants mostly build a house part by part

I try to track the trail of hope that is left by the migrants in their original places. One of the houses I visited during six months of fieldwork in East Java, has an unusual high ceiling. The owner of the house told me that he wanted to build a two-story house using the remittance, but in the middle of construction, he miscalculated the cost.

“Give me forty million rupiahs and I will finish this house…” he said optimistically.

When he realized he couldn’t finish the house, he chose to prioritize his mother-in-law’s bedroom. Those rooms become the only rooms that have ceramic floors. The house that migrants build is a sign and proves that they are already successful as migrant workers.

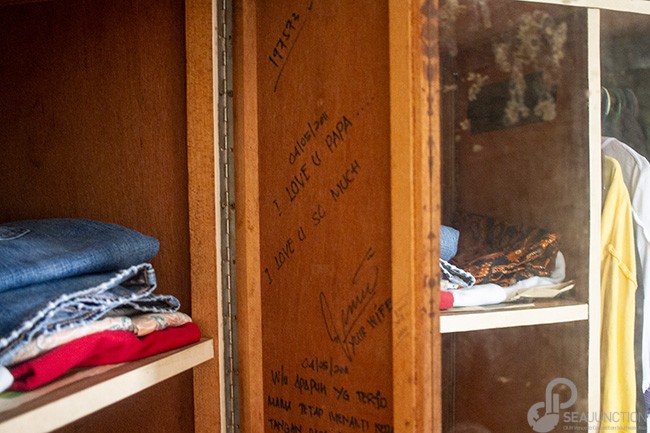

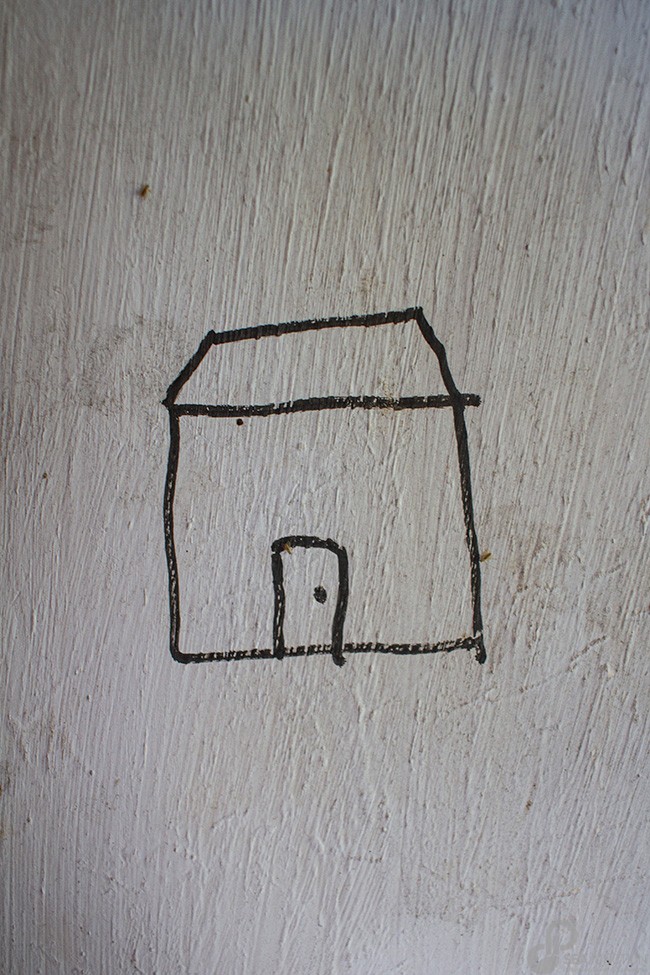

Building a house is like a ritual for the migrant workers in the village and a way to communicate with the people that they left at the house. Drawing on the wall, the number of rooms they made, the ornament they put, also unfinished building structures became the migrant trails of hope.

migrant husband video calling his wife who is become migrants worker in Singapore. He showing the goat that he buy using the remittances

an Indonesia migrant worker going out for work in Malaysia

ex-migrant worker standing on her field that she buy using migrants money

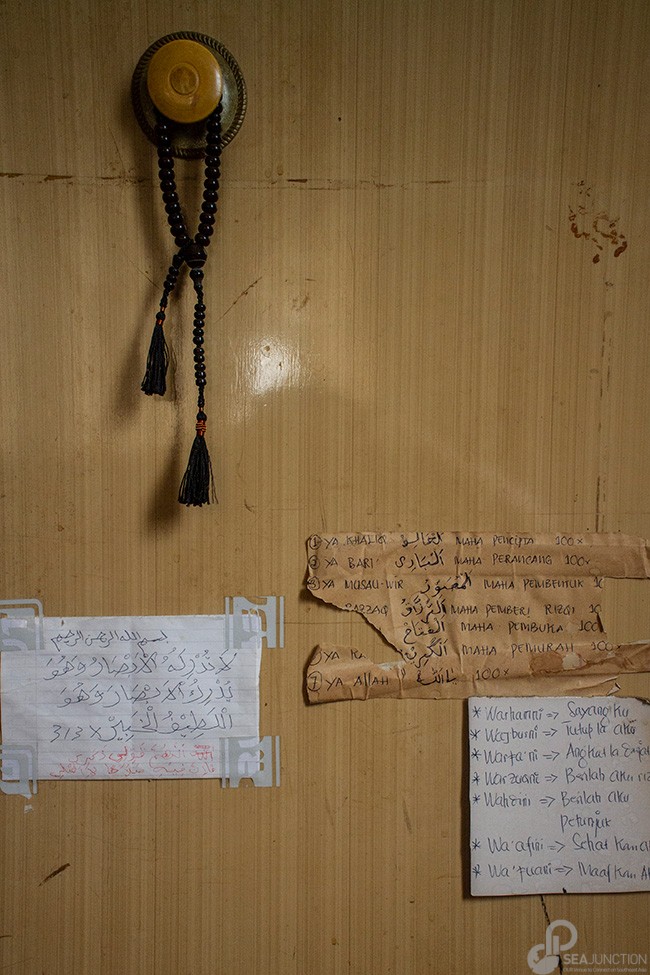

amalan (prayer) on of the migrant room in Malaysia. A lot of migrants having special prayer from religious figure or shaman for giving them safety

the area where most of the Indonesian migrants stay at Malaysia. In the background is the famous twin tower

At the migrant destination, I am observing the life of migrant workers in downtown Kuala Lumpur. As not I expected, they are a very loud community. Most of them will work as construction workers during the day. At night they will gather in a small warung (Stall). Those times are when people express their worries, their problems at home, how to pay for permit extension, or how long they will live this kind of life

migrants houses in Malaysia

the migrant worker took me around and showing me the twin tower. He explain how his friends was part of the construction worker team

fireworks from wedding of Indonesian migrant worker and Malaysian citizen

In the end, it is not a problem of how big the migrants can get money. The government needs to pay attention to the matter of hope. How to nurture people’s hope, what people aspire to, try to bring more options to the people and let them choose. The worker migration system that only circles on the hope of the state, will only give people false success and turn the actual problem into a ghost, that people can’t see and think about.

a message on the migrants wardrobe

red brick being prepared for construction of migrant house in Indonesia

drawing on the wall of migrant house in Indonesia

a group of people trying to build road together in migrants origin area of Indonesia

Biography:

Yuniardo Muhammed Alvarres is an undergraduate student studying Cultural Anthropology from Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia. With a passion for photography, documentary filmmaking, and storytelling, Varres is drawn to capturing and sharing stories that shed light on important social issues. Specifically, he is interested in exploring the complexities of migration, the impact of violence on communities, and the formation and negotiation of identity. Through his work, Varres aims to raise awareness, foster empathy, and reflect his experiences. To experience his stories, found him at his Instagram @yuniardoall or explore his website at www.varres.id.

Organizer:

SEA Junction, established under the Thai non-profit organization Foundation for Southeast Asia Studies (ForSEA), aims to foster understanding and appreciation of Southeast Asia in all its socio-cultural dimensions- from arts and lifestyles to economy and development. Conveniently located at Room 408 of the Bangkok Arts and Culture Center or BACC (across MBK, BTS National Stadium), SEA Junction facilitates public access to knowledge resources and exchanges among students, practitioners and Southeast Asia lovers. For more information see www.seajunction.org, join the Facebook group: http://www.facebook.com/groups/1693058870976440 and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @seajunction

In collaboration with:

The JFK Foundation in Thailand was founded by H.E. Dr. Thanat Khoman, the former Ambassador to the United States, with the purpose of commemorating President Kennedy’s principles.