Photo essay for the Special Initiative “From Fear to Resilience: Visual Storytelling of COVID-19 in Southeast Asia” by SEA Junction and Partners.

| Title: | The Philippines’ Face Masks: Protecting Health, Celebrating Identity |

| Storyteller/Photographer: | Diana G. Mendoza (with additional photos provided by the artists as indicated) |

| Place: | Quezon City, Metro Manila; Davao City, Mindanao; Iloilo City, Visayas; Kiangan, Ifugao Province and Abra Province, Cordillera, The Philippines |

| Time: | July 2020 |

“Behind every mask, there is a face; and behind that, a story,” Marty Rubin, an American writer and gay activist.

The frantic search for face masks began as soon as the Philippines capital and other regions went under lockdown in mid-March. The stocks of face masks that were meant for disasters dwindled after Taal Volcano south of Manila erupted in January at the same time the coronavirus scare began.

But three months later, various versions of the protective piece of cloth proliferated, providing more options to people on lockdown. Some Filipinos who suddenly found themselves without work and income thought of producing face masks out of fabrics – from cotton to linen to polyester – and selling them on the streets and online. The cloth masks immediately became reusable, washable alternatives to the disposable medical and surgical masks.

What happened next was even more pleasant: the emergence of face masks made of indigenous, traditional fabrics, mostly long ignored by Filipinos who may have forgotten that their birthplaces had emblems that symbolize their history and identity. To date, over a dozen weavers and producers of face masks have revived the fading but rich heritage of the Philippine archipelago – a most welcome change to stir up patriotism at such an extraordinary time of a global health crisis.

The most common way of designing is weaving – a part of Philippine culture even prior to its Spanish colonizers. Elder community leaders see weaving, a method of textile production, as eminent and sophisticated. It entails interlacing two sets of yarns into right angles to construct a fabric. Materials can be anything from abaca, bark, coconut, cotton, pineapple, to name a few. The materials, colors, designs and embroidery of each province or region symbolize people’s rituals, beliefs in gods and spirits, norms, and traditions. Clearly, Filipino identity and ingenuity – and the desire to help make the ill planet a better place, has evolved.

From Mindanao in the south, Windel Mira, who has been in the fashion industry for 16 years, decided to make face masks during the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) in Davao City. “We were forced to close shop and stop operations, but since face masks have become essential, I decided to make my own version,” she said. Mira used some of her retazo or snippets of remnant cloths from previous fashion shows and made them into face masks, infusing Mindanao’s traditional fabrics including decorative items such as beads. There are hundreds of indigenous textiles in Mindanao; to name three: inaul, the traditional woven cloth in Maguindanao, dagmay of the Mandaya and t’nalak of the T’bolis.

Mira said there was no better time to also help continue the livelihood of the sewers and weavers since all projects have been cancelled. “I wanted to create face masks that showcase Mindanao’s identity and culture,” she said. “The art of weaving is one of our old traditions. Every pattern, color and texture represent the identity of the tribes and indigenous peoples in Mindanao. These fabrics have a big significance to our identity as Davaoeños and Mindanaowons,” she said.

As of this writing, Mira has produced 25 pieces of face masks bearing Mindanao’s diverse indigenous patterns. She explained that it takes time to finish one mask because “the materials are very sensitive; you have to be extra careful.” The 25 face masks are each designed intricately and are reproduced per day at 50 pieces each. But she is overwhelmed to have countless local clients already and many buyers all over the Philippines and the US. “I will produce face masks from indigenous fabrics for as long as people will need them,” she said.

In the Visayas region, designer Jaki Peñalosa of Iloilo City, who has been designing clothes for more than 30 years, volunteered her shop in making personal protective equipment and face masks for the city government and the Philippine Chamber of Commerce-Iloilo while on lockdown.

She has produced over 1,000 face masks made from hablon, Iloilo’s traditional textile. “Hablon helped Iloilo open itself to world trade in the mid-1800s as its unique texture and shine captured the Europeans’ discriminating taste for the unordinary,” she said. Hablon, a word in Hiligaynon, one of the languages in the Visayas region, refers to both the weaving process and the finished fabric. Weaving used to be a major industry in Iloilo until it was overshadowed by the more lucrative sugarcane production. But with Peñalosa’s hablon face masks and the efforts of other designers and weavers, the tradition is being revived.

“For as long as the COVID-19 threat is around and for as long as people continue to want to look better than how ordinary facemasks currently make them look, I would continue producing face masks also because I see a new market overseas,” she said. “This way, my hablon advocacy becomes not only more meaningful but truly rewarding as well.”

In the upland province of Ifugao in the Cordillera region, producing hundreds of face masks became immediate for the Kiyyangan Weavers Association (KIWA) when the island of Luzon went on lockdown in mid-March. The volunteer organization Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement (SITMo) bonded traditional weavers from the towns of Kiangan, Hingyon, Banaue, Lagawe and Asipulo to sew face masks from woven fabrics for their farmer members.

Marlon Martin, SITMo’s chief operating officer, said the group’s brand name “Ifugao Nation” is still being registered, but they made masks for the farmers’ use. “As the costs of regular surgical masks went high and many of our community members couldn’t afford it, we called for volunteer mananahis (sewers) to sew our fabrics into masks. We gave 3,000 pieces free to the community,” he said.

Ifugao is known for its world-famous Banaue Rice Terraces. Martin’s organization is a heritage conservation group mostly of rice terraces farmers. “Heritage conservation is a matter of economics for farmers and traditional artisans.” Since many of the farmers are also craftspeople, they came up with KIWA, which started with 15 elderly weavers, then 45, and still growing. “Many of our weavers now are young people, so the heritage continues,” he said. Ikat is Ifugao’s most known traditional weaving that involves dyeing yarn with stripes and diamonds designs.

Martin said traditional weaving of the Ifugaos was consumed by the market economy and forced weavers to sell their products at very low costs, with retailers getting twice or thrice the profit — the usual capitalist tendency of the artisan getting the least profit in the market chain. “We wanted to change that and change we did. Our organization pays the highest in terms of labor cost for weaving.”

“We will produce face masks for as long as there’s a public need for it,” he said. “We stopped counting at 10,000.” Selling started in June when they were swamped by requests. “We can barely cope with the demand now, which is a good problem. Most of our buyers are from Metro Manila and we get regular requests from abroad. We shipped as far as the US and Canada.”

Martin added that in keeping with the “heal as one” call of the times, “we do not intend to make our masks as expensive as what others are doing now. P500 to 1500 for a single woven face mask is profiteering already. In making our masks, we make sure of the quality, putting safety over aesthetics.”

Farther north in Abra province, Luis Agaid Jr., chairman of the cooperative and project coordinator of the School of Living Tradition Local (STL), said his group produces 150 to 200 faces masks a day, with buyers from all over the country and abroad.

They use abel, the province’s weaving technique of traditional arts patterns but with varying techniques and designs. “In Abra, we follow the traditional patterns that we grew up knowing. It’s our heritage,” he said.

Agaid’s organization also serves as the coordinating team of the government’s National Commission on Culture and Arts that helps communities strengthen cultural pursuits. His community has been engaged in abel design especially on woods and clothes for 40 years. He thought of making face masks when he attended an international fashion dialogue in early March in Cebu City.

“The fashion industry was having difficulties when the pandemic was inching closer, so when I came back, I told my colleagues in the coop that we needed to adjust. We needed to start producing face masks,” he said. They waited a few days due to the enhanced community quarantine before they started working. “We all worked in our own homes. By the time the lockdown was relaxed into a general community quarantine, we marketed our face masks.”

His group also teaches the young and old alike on traditional arts and culture, with revival dye weaving as one of its newest lessons. “We will teach for as long as people want to know our culture. We will make face masks for as long as people need them,” he said.

Storyteller/Photographer

Diana G. Mendoza is an independent journalist based in Manila, the Philippines. She contributes to local and international media outlets. She is an associate producer and head writer of One News Cignal TV Philippines, and co-founding editor and managing partner of Women Writing Women Philippines, a news website that provides a voice to the stories of women and girls. On the side of journalism, she engages in communications and editing work for regional and international advocacy and development organizations.

Photos of the artists and their works were provided by the artists, namely Windel Mira, Jaki Peñalosa, Marlon Martin and Luis Agaid Jr., as indicated below.

Organizers

“From Fear to Resilience: Visual Storytelling of COVID-19 in Southeast Asia” is a special initiative of SEA Junction and its partners Beyond Food, GAATW and Bangkok Tribune to promote an alternative narrative of survival, resilience and solidarity. For more background and other stories click here.

A black medical face mask thrown on the pavement in Quezon City (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

A cleverly-designed face mask thrown away along with tissue papers in Metro Manila (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

A medical mask on the ground of Quezon City, Metro Manila (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

A cloth mask discarded on the street of Quezon City (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

Disposable medical masks sold at SM malls in Metro Manila (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

Various versions of the cloth masks for sale in Metro Manila (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

Sale of face masks along with other stuffs on the street of Quezon City (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

A vendor selling face masks on the street of Quezon City (Photo by Diana Mendoza)

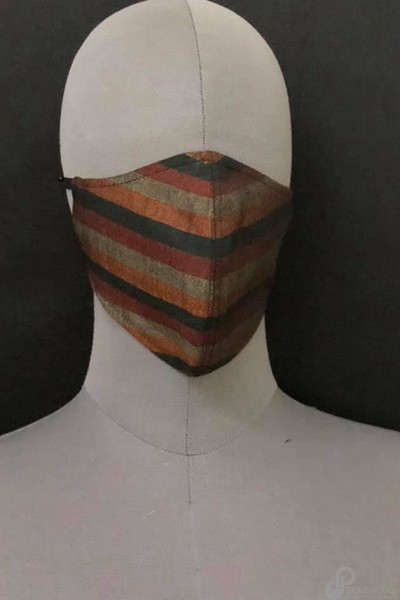

Face masks from Mindanao (Photo provided by Windel Mira)

Combining color and heritage of Mindanao (Photo provided by Windel Mira)

Some of Windel Mira’s Mindanao culture-inspired face masks (Photo provided by Windel Mira)

Some Mindanao traditional beaded face masks (Photo provided by Windel Mira)

Windel Mira at work in Davao City, Mindanao (Photo provided by Windel Mira)

Iloilo’s traditional hablon face masks (Photo provided by Jaki Peñalosa)

Black series face mask from handwoven pineapple fiber made by Jaki Pentalosa in Iloilo City (Photo provided by Jaki Peñalosa)

Iloilo’s hablon face masks (Photo provided by Jaki Peñalosa)

Iloilo’s reusable handwoven pineapple fiber face mask with cotton lining and pocket (Photo provided by Jaki Peñalosa)

Two girls show dresses and face masks made from Iloilo’s patadyong (Photo provided by Jaki Peñalosa)

A line of Ifugao masks (Photo provided by Marlon Martin)

A full Ifugao textile mask with a matching head cover (Photo provided by Marlon Martin)

A woman weaving a green Ifugao textile (Photo provided by Marlon Martin)

A girl learning to weave Ifugao textile (Photo provided by Marlon Martin)

Men making masks in Ifugao (Photo provided by Marlon Martin)

A woman prepares to sew face masks in Abel design, Abra province’s weaving technique of traditional arts patterns (Photo provided by Luis Agaid Jr.)

A mask with intricate Abel design (Photo provided by Luis Agaid Jr.)

Abel face masks with pockets (Photo provided by Luis Agaid Jr.)

Boys wearing the face masks that they helped make in Abra Province (Photo provided by Luis Agaid Jr.)

Family members help make Abel face masks (Photo provided by Luis Agaid Jr.)